Chapter IX - The Need to Be Whole

we need to be humble, or maybe we become humble reading Wendell Berry.

This is the ninth discussion entry into Wendell Berry’s, The Need to Be Whole: Patriotism and the History of Prejudice.

Share your comments below—this is intended to be a community conversation.

Chapter IX. Words (40 pages)

To Be Humble …

When the end is near in a book of 513 pages it is easy to want to rush through the closing paragraphs. Berry does not permit that submissive appeal. One way is by his truth in the first sentence of this final chapter.

I have spent many years working over the grounds of an agrarian indictment of the industrial destruction of the land and of its natural and human life. (447)

With this petition of effort, why wouldn’t the reader support the author in finishing his thought?

I have tried to adhere to my belief that the right model or the norm of human relations is a conversation in earnest and in good faith between two people. When enough conversations of that kind are taking place across the racial divide, I assume, the divide will be no more. On that assumption, I have tried to write what I could honestly consider my part of a conversation, in which one thought naturally would invite another thought, perhaps a counterthought, or one story would be a reminder of another story. In some places, my side of the conversation has been disagreement, pointed and plain, but expecting a reply equally pointed and plain, and with perfect willingness to argue face-to-face with my opponent. In fact I would like, and would relish, a good deal more response than I have so far received from my opponents—to whom I have never wished any harm. (448)

This is the community conversation to which Berry asks from each of us. Part of why my reading The Need to Be Whole offers the words of others in participation. Not to broaden the appeal of like-mindedness, which to be sure is validating but not conducive to change without the dissimilar. We need solutions, true justice and that requires leadership. The hardest conversations are those that begin at home, with the people that live in the house next door or down the street or four streets over. Where are agreements found and what is the background of the divisions? Are those divisions mere misunderstandings or long-held grudges or convictions rooted in personal experience hard to define?

Of course, Berry is talking about race—black, brown, white—less often red. Skin colors. He toils into class—blue and white. He plods into spaces—rural and urban. He deciphers—specificity and generalizations. He toes the spiritual line of sin while also allowing a broader definition to right and wrong. He frames—perspective as something every individual has and relies upon, and that no two individuals experience life the same.

What of these words, these thousands of words matter? For some, they don’t—the text is not meaningful, it does not correspond, life is too busy to look at other vantage points because present is the only company. For some, the words do—the text is meaningful, it does correspond, life is busy but change begins with self and sharing words with others. Building a new, better, thoughtful community.

Community is permitted disagreement. I sometimes feel that others perceive Berry as being in a utopia fantasyland of nothing but accord. I don’t think Berry’s worldview is this at all, but it is a treaty and promise. The treaty is an agreement to do the greatest good possible for all members of a community. The promise is in that expectation of action and behavior.

My Effort to Build Community

On our homestead we produce not all but a significant portion of the food we need. Does it often mean potatoes, carrots, onions, and cabbage in the winter season. Yes. Do I tire of them, not really. Creativity is a generous package, and the pantry has lots of other goodies from the summer season bounty. The food we raise from the beds of dirt we tend gifts our home as well as friends and acquaintances. Still, I am fascinated when an offering of a red-leafed salad head is met with disinterest, “I’ll just get it at the grocery,” or the bags of granola I sell is rewarded with a crinkle of the nose, “This is too expensive.” What are the expenses we extend to our community by purchasing the Lucerne cheese that is made in California when we have dairy farms (literally half a mile distant) with milk. 94 farms in Vermont sell their milk to Cabot for cheese, why would I buy cheese or milk or cottage cheese or sour cream from farmers 3,000-miles distant. The expense is fuel and refrigeration, extra costs, environmental costs. Community is supporting the nearby farmers by buying milk from their side-of-the-road refrigerator.

I woke in the middle of the night to write—dangerously distort our land. The conversations I was having with myself at 2 am wasn’t about farming (it applies), mining (also applies), war (in a generalized frontage), but conversation. How it sways to scrap and devalue knowledge—institutional, cultural, personal, community—also collective wisdom, shared understanding, accumulated experience, and memory. For the past couple of months, I have been prone to say, “The last man standing is holding a carrot and one bullet.” Only then will nature be permitted to replenish what is depleted, structures will fail, rivers will run free, forests will balance with variety, the soil will devise ways to balance the toxins. What a dispiriting way to look at the future. There is no equality in a destructive economy or places where people live but have no home, only a domicile and have no community, only driveways that lead to front doors of people they don’t know.

When we bought our Vermont home I delivered an invitation to the mailbox of our neighbors. The invitation was a “Get to Know Your Neighbor” feed. We wanted to avoid the: when do you stop by, is bringing a gift necessary, thing. Come over, let’s eat and drink and get to know one another. It was friendly and we met our immediate neighbors which expanded to know more of the people who live in the homes that abut dirt roads. Some we are friendly with; some we are not. We support where we can. Once I dropped a cooler with a note and homemade goods inside for a couple living in an RV after fire ripped through their century old farmhouse. The note, “I suspect you miss homemade goodies from the oven about now,” or something similar. I’ve never met them, but the cooler was moved to the end of the driveway and when my husband stopped to pick it up, he had a long conversation filled with gratitude and history and fellowship. Someday, I will meet them but even if I don’t, community includes a built-in sharing and offering. When there is a need, it arrives. Community is serving to one another.

Does Berry say any of these things. No, not necessarily or at least not directly. Community is barter, give and take, hard work, self-sufficient industry. Community is co-opting a cow, picking blueberries from a friend with excess, returning with a jar of jam, sharing the extras with the elder gentleman who lives alone. Community is locking the front door when zucchini becomes a serious game of leave and run, plowing a driveway when the owner’s tractor is broke, volunteering on committees that makes local governance a priority. Community is attending potlucks with a homemade meal, delivering a food basket and warm blanket to parents with a new baby and not a lot of extra for the propane bill, or baking bread and pairing it with a quart of soup to a neighbor in chemo. Of course, one must know their neighbors for this engagement.

None of Us Live in a Silo

The argument is that we can’t go back, but maybe a replacement argument is to seek a new way forward. Dan shared an example from a friend in the comments of Chapter VIII, how the physical health and chronic conditions of the pastor’s parishioners impacted the community and the regularity of standing in the pulpit with a eulogy of people too young to die. Poor health is endemic nationwide, reliance for better health found in a pill but does that work? Is there another option. Yes, in Dan’s example, a healthy eating initiative, garden—move in the garden, tend the garden, grow the food, eat the food, save a few dollars. And then there is the social, self-sustainability community component. Will there be critics, of course. Are the complaints unfounded, I think so. Those are probably the same people who want to purchase a red-leafed head of lettuce from the grocery. To enlighten people is not an exercise in futility though it might sometimes feel like it. Like seeds in a garden, conversation grows.

What does any of this mean in Chapter IX Words?

Any combat or conflict that divides people into winners and losers really never ends but only keeps the problem alive. (449)

Berry reminds the reader that equality, a chapter discussion hundreds of pages distant, fails to exist when the land is destroyed, and communities are degraded. This is the agrarian backbone, the rows of tobacco, potatoes, or watermelon of the book and it

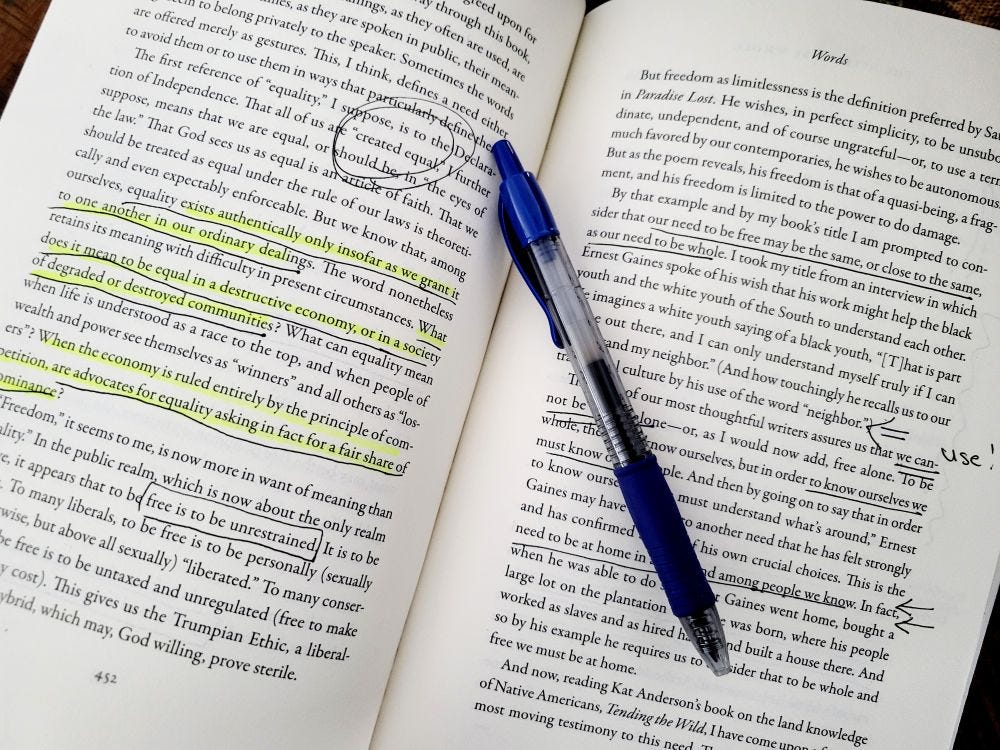

… exists authentically only insofar as we grant it to one another in our ordinary dealings. … What does it mean to be equal in a destructive economy, or in a society of degraded or destroyed communities? … When the economy is ruled entirely by the principle of competition, are advocates for equality asking in fact for a fair share of dominance? (452)

I appreciate Berry’s use of the word “dominance” which by definition means to dominant which means to command, control or prevail over all others.2 In fact, I might begin to use this word as more a direct, reveling in its confrontational feel as it rips off my tongue because I tire of the words so kindly used-to-tired in our treatment of the land and one another. To dominate is to feel capable, strong, valuable often to mask an insecurity. But value is in community—stay with my logic—when there is no value to community, the bare existence of individuals is laden with insecurity and fear and vulnerability—traits that rise as unacceptable posturing.

Berry’s argument comes full circle in this chapter. In Part 2 of Chapter VIII, Jody writes about, “Berry’s lumbering logic chain.” The last forty pages, which many are grateful for in its brevity and that the pages on the left are of greater heft than those on the right because readers are tired, brains bruised, and self-analysis is a burden. It is a feat. There are agreements and disagreements to rigorously decipher what could have been a one sentence book. One that repeats a sentence we should know.

The quotation "all men are created equal" is found in the United States Declaration of Independence and is a phrase that has come to be seen as emblematic of America’s founding ideals. 3

Until we are not.

To be whole and free we must be home. Freedom needs a better meaning, says Berry. Maybe we should look at what freedom means to us as individuals and compare notes.

If to be whole and free is to know oneself in part by knowing others, and to be at home in a place and a community where one knows and is known, this implies the further need to be self-disciplined and reasonably self-sufficient so as to have both the wholeness in oneself that is health and also freedom from being a burden or a nuisance to other people. (454)

I like the word nuisance (a bit of Berry humor), which in my deciphering also means if you aren’t a participant then you don’t get the benefits of a community which has a circle logic in and of its own.

How do we,

… develop local economies fitted to the natural limits, requirements, and advantages of our home landscapes? (455)

Where are the mobility ties in our current social current, the fabric with holes of disconnect. Using the particular words of Berry’s dissection of Patriotism and the History of Prejudice, Berry revisits economic growth in the final pages which builds on the chapter of Work. What we have shared as a communal read for the past two weeks is eerily codified into:

… we made violence the norm of our life. (461)

It feels necessary to close this discussion, this reading as it were, with activism. Berry points fingers,

… we sustain our wish to change the world without changing ourselves. (464)

Thereby it is time to, privately, he encourages,

… question our lives and our ways of living. (464)

We are a species in need of integrity, a firm adherence to a code.4

As Berry draws down with a final gasp of human and humanity, reflect on the pages to prejudice, its degrees; work, its collars; economic malfeasance, peons and barbarity; and the land community, degraded and mistreated.

The point, now, ought to be obvious: The earth that we are laying waste, presumably for our benefit, is neither human nor separable from humans. (472-473)

Berry set the stage for this tome. He used the word all. He made a point of including a founding document of our country as the second sentence in Chapter 1. Did you notice that he included [humans] when he quoted from the Declaration of Independence, or did you forget? This is no accident; he affirms our rights. Our rights include wholeness.

The road has been twisty, but the dots are connected, when we fail/failed to treat one another as equals. We each have something to offer. The land, our substantial supporter, too suffers. What we do to the earth we do to ourselves.

As we are not whole in our selves when divided from other humans, so we are not whole as humans when divided from all other creatures, so we are not whole as creatures when divided from the earth, from a home country and the landmarks and reminders of a home country. These connections we need to know, understand, imagine, and live out. Thus we complete our story as members and as persons. This is the wholeness that we long for, that we hear about from our forebears and our prophets. This is the work we are called to, individually and all together. (484)

Our inactions, our actions, our treatment:

… cannot be exonerated or excused. (464)

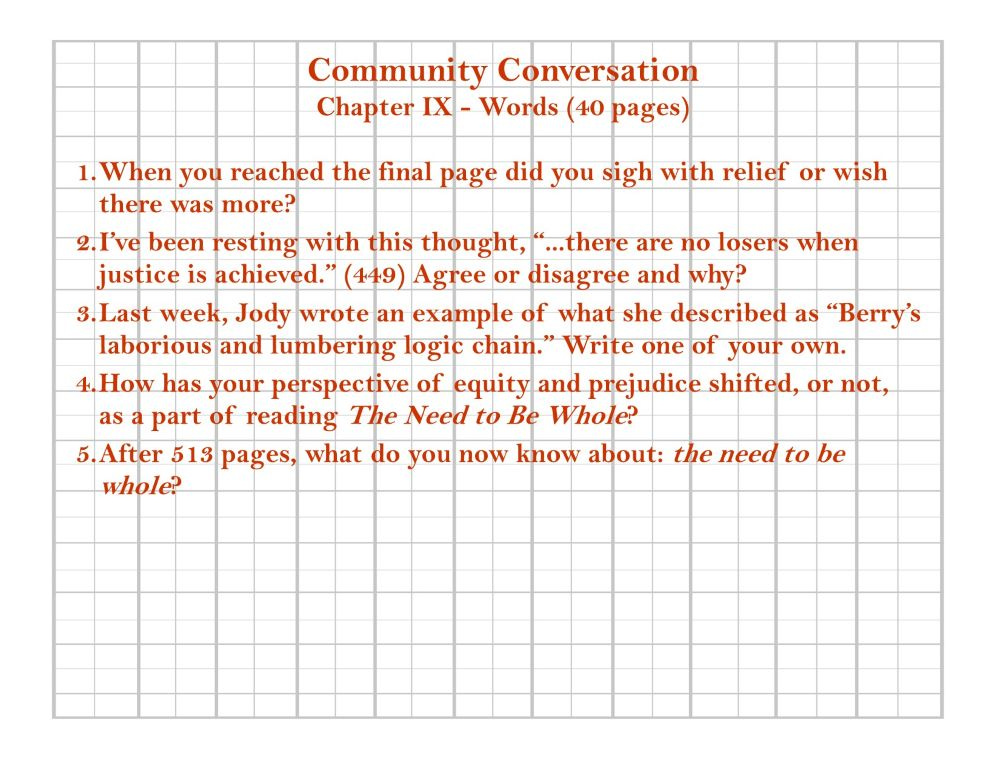

March 16 - Community Questions

To close out this discussion of Wendell Berry, I asked the Jody, Dudley, Mary Beth, and Sarah five questions in reflection of their experience reading The Need to Be Whole.

Also, in the past many weeks I have found a few writers with essays and reflections that support the agrarian theme. I’ll compile five or so (like the link below) that you might want to check in on now and again.

Share Your Thoughts

Reading Berry is to understand he values community. Please share your thoughts in the comment section and we can have a community conversation.

Don’t know what to type? How about what you liked about this final ninth chapter or what frustrated you. Share a quote that resonates. Maybe something you have learned or any of the principals Berry touches upon. Other possible questions are below.

References

We are reading Wendell Berry’s, The Need to Be Whole: Patriotism and the History of Prejudice. Shoemaker & Company, 2022.

Now that we are at the end of Chapter IX, and happy to have arrived there with huge thanks to Stacy for bringing us together, I'm delighted that the conversation is expanding into neighboring territories. Meeting up with Jayber Crow again in James M. Decker's West of 98 is one reason why. In that spirit, I'd like to share the following which came to my inbox via Undermain, an arts advocacy non-profit in Louisville. Remember Crystal Wilkinson, the writer Berry introduced us to in Chapter VIII? Here she is again, joined by the poet Frank X Walker, in a conversation about what it means to be a writer in Kentucky, in a state with many great writers whose connection to the land is central to their work. https://undermainarts.org/ky-writers-hall-of-fame

One of my best friends handed me Jayber Crow the other day, saying he thought I'd like it.