Chapter III - The Need to Be Whole

when shadowy figures emerge into light, says Wendell Berry

This is the third discussion entry into Wendell Berry’s, The Need to Be Whole: Patriotism and the History of Prejudice.

This week there are two essays. The first from Dudley, the second from Stacy.

Share your comments below—this is intended to be a community conversation.

It is with great pleasure that Dudley of The Hidden Pond Substack by Dudley Zopp | Substack, joins this introspection with an essay on Chapter III. Degrees of Prejudice.

Dudley Zopp (she/her) is a visual artist, habitat fixer, lover of languages, and student of the Tarot. She grew up in Kentucky, fascinated by goings on in the natural world, and has been painting and drawing to understand that world for most of her life. In 1996 she moved to Maine and for the past 18 years has lived just a short walk away from the eponymous Hidden Pond of her Substack, where the natural world is always changing according to the seasons and where a growing number of animal and plant species now find a home.

In the studio, Dudley’s drawings and paintings straddle a line between abstraction and representation, and her artist’s books are sculptural, often based on magic tricks like the Jacob’s Ladder. Dudley comes to the Tarot with the dedication she has brought to learning French, German and Spanish, and uses her knowledge of languages to communicate our responsibilities to the earth.

I am mesmerized by her work, intrigued by her artistry, and in love with The Blue Marble Book. Find her work here.

Chapter III. Degrees of Prejudice (88 pages)

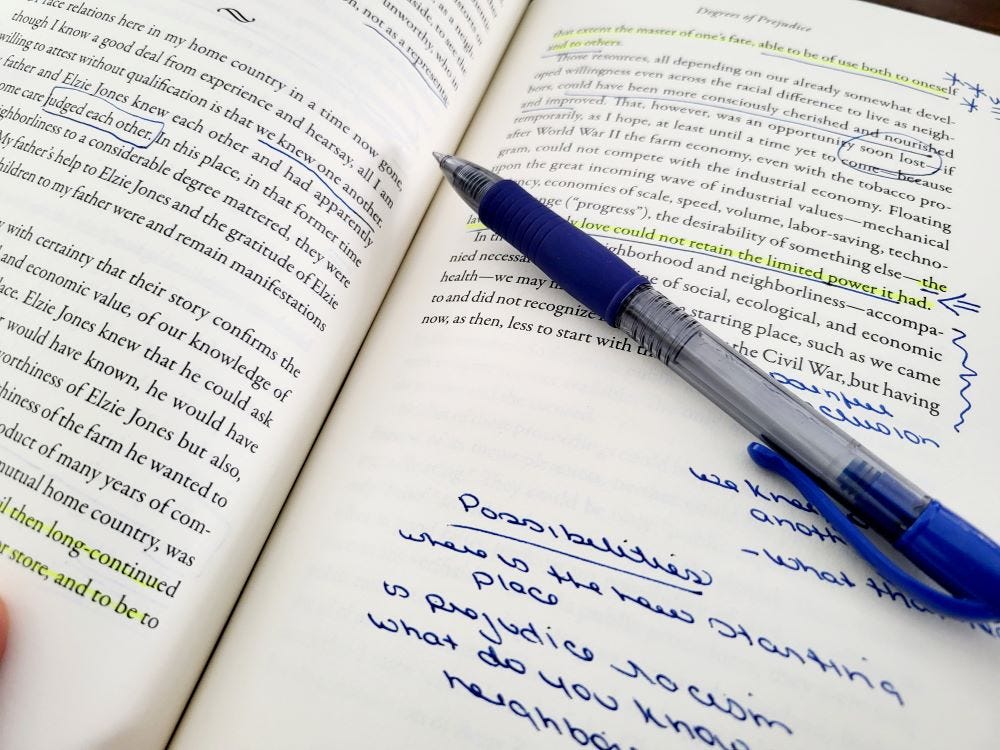

Dudley’s Essay

When Stacy was planning the schedule for us, I right away stuck my hand up for Chapter III. I wanted to understand my own experience as a native Kentuckian who is only a few years younger than Wendell Berry, and I hoped for clarification of the changes in Americans’ acknowledgement of what it means to be racist.

In Chapter III, Berry examines the “degrees of prejudice” of his experience. To do so, he looks back to ancestral memories of Kentucky’s position as a border state in the Civil War, and to the aftermath of the war under occupation by Union troops, and the general lawlessness of roving bands of night-riders. Moving forward in time, he considers what it was like to live as “Two Races In One Place, One Time,” and then narrows the focus to individuals whom he knew and worked with.

White children learned the racial differences more or less by absorption as they grew up. That, anyhow, was the way I learned them—except that I was strictly and deliberately instructed to be considerate of black people’s feelings. (101)

In the final section he writes:

My title for this chapter is ‘Degrees of Prejudice,’ which I believe is a real subject but one extremely difficult to talk about. We are dealing, it seems, with amounts verifiable by experience but impossible to quantify. (128-129)

Throughout The Need to Be Whole, I see the same fidelity to accuracy that I have known in other Kentucky writers/historians, and that I hope for in myself. I note Berry repeating his arguments over and over, attempting to get at the truth, or at some way of resolution, by looking at a thing from all sides.

As someone noted in the comments last week, context is everything. Here is mine. I grew up in the then small city of Lexington, in central Kentucky. On my father’s side, my great-great-grandfather was a cabinet maker and owned a few slaves. He and his sons supported the Union. Three of those sons fought in the war and one of them was killed.

Another of those three sons was my great-grandfather, who was an abolitionist. In contrast, my mother came from Mason County, Kentucky, where her father raised tobacco and cattle on a small farm along the Ohio River. His father too had owned slaves, but again, not many. It seemed curious to me as a child that my mother’s family had been Southern sympathizers even though they lived well to the north of us.

Against that background of small farms and small cities, in a border state that never seceded, there was no animosity on either side of my family toward Black people. My brothers, my cousins and I were taught to be courteous within the family and toward neighbors and strangers. It’s important to me, as it is to Berry, to acknowledge that when those relationships were personal, as in the case of people who worked in our homes and on our farms, there was often genuine affection on both sides, one for another. One of the people I remember best is Laura Washington, who was my grandmother’s cook and housekeeper next door to us. I spent time with her nearly every day, watching and learning. Another was Tom Carter, the groom who took care of two horses for a family on our city street. I was often there, drawing the horses and listening to his stories and advice. He always concluded by saying, “Now when you grow up, you remember old Tom Carter told you this.” I wish I could remember exactly what that was. I suspect it had to do with how people treated each other.

There can be no excuse for slavery, either in the past or in its present industrialized forms. That makes it difficult, across the generational distances of time and the geographical ones of place, to convey that person-to-person affection in such a way that it is believable to today’s readers. Nonetheless, it existed and should be acknowledged, because such relationships are starting points for coming together again.

The stereotype of racial prejudice … is racism, an absolute. The only telling thing my several instances have in common may be that by their differences of degree they dissolve the stereotype, showing how little it explains. (129)

For a long time, I believed that racists were other people, the Klan and people like today’s J-6ers. Now I see that nearly everyone I knew simply looked past, whether unintentionally or consciously, a mindset rooted in colonialist values. The scales fell from my eyes when I visited the newly opened National Museum of African American History & Culture in Washington, where 400 years of pain and achievement are presented in moving detail. Since Brown v. Board of Education, and the marches and protests of the sixties, huge strides have been made toward societal equality, while individual positions have hardened and coagulated into subcategories made up of people who share our likes and dislikes. It is also, as Berry points out repeatedly, difficult to practice human values in the midst of a mechanistic society. And yet:

Black experience and white experience overlap in human experience and this shared experience is greater, more significant, and more promising of good than all the differences. (27)

Berry and I write from that shared human experience. We grew up in a politically, economically and racially divided state, a state with six distinct geographical regions, stretching from the Appalachians in the east to the Mississippi River in the west. In its many-faceted divisions, Kentucky may serve as a microcosm of the United States.

Berry’s point is that families and communities have worked together in spite of political and economic divisions. Can we return to an agrarian society? Not any time soon.

Instead, it is up to us to create new patterns of working together.

In the decline of neighborhood and neighborliness—accompanied necessarily by the decline of social, ecological, and economic health—may we finally recognize a starting place, such as we came to and did not recognize in the ruins after the Civil War, but having now, as then, less to start with than before. (131)

Stacy’s Essay

It might feel like reaching this chapter allows for a moment to catch one’s breath, the first two chapters, and even the introduction being a weighty blanket to carry. What Berry offers in this chapter are essays that can be taken as bite-sized reads. What I wish Berry had done was make Essay 10. Degrees the first essay. Not as a cop out, but as a way to hold his feet a bit more into the fire of this conversation. Nevertheless, I do feel a bit of tenderness when he says:

So was the old and until then long-continued wish to possess one’s own small farm or shop or store, and to be to that extent the master of one’s fate, able to be of use both to oneself and to others. (130-131)

Wish – impose or please or request? I think wish as in purpose, as in community. The entire last essay is as full of ink as the first essay (1. My Old Kentucky Home). The conclusion is a painful one.

… the law of neighborly love could not retain the limited power it had. (131)

What is this collection of essays? A walk down memory lane? A reflection of past times? A glimpse into an era full of wrath and distrust except it wasn’t that way everywhere. There were places of kinder and gentler and front porch sitting.

Is this section an aging man sitting in a rocking chair surrounded at his feet by ghosts who listen. Different from the previous two chapters where lecturing comes from a podium and maybe an accompanying handwritten handout with dots to be connected and the center being “the farm.” The lecture from the first two chapters is long overdue. Chapter three considers history while at the same time considers the relevance of memory, often only found in pieces of saved letters, relationships outlived, and the understanding that Berry’s beginning with the Civil War that in Kentucky was “a brothers’ war” as described by Shelby Foote. A divisibility likely constrained within an idea that:

… he [the slave] has been reduced from the human relationships he experienced at his home in Kentucky to the true hardship of a man valued only for his work. (50)

Whereas Berry is speaking directly about Stephen Foster’s, “My Old Kentucky Home, Good Night!” the analysis, it seems to me, is the center point of all slavery conversation. More to the point, there is no history other than that which has been passed down and its only interrogation can be from what is “reduced and revised by perfunctory political correction.” (54) But what we might not want to remember is that history belongs to those who lived in a time and the author, his memories which might be different, or even contrary to general belief, are memories that is something other than the present. I think what I am saying is that there is a collective memory and that understanding such is also to understand that today is different from yesterday.

In this chapter, essays range in a way that gives value to a burden that we all must work within to rebalance the scale of discontent—our own and that of others.

… a big problem for us that we have so nearly succeeded in obscuring the real complexities, ambiguities, and enigmas of our history by way of silence, ignorance, and the cliches of progress and self-righteousness. (56)

Not that I want to misuse the term of whitewashing, but these memories help to border our own prejudice while at the same time putting forth an argument that there is a generation of men born post-depression and in the beginnings of WWII who really might have truly been or remember being better in their relationship constructs. Because I do not believe we all wage or harbor a resentment towards another from a single observable characteristic. And if the undertone of this entire book is anything, might it be that we should press back on the push of inequality which is a prejudice?

I think of my grandmother who horrified me with her use of racial slurs, particularly when out eating dinner within the ears of those who could hear. Can I excuse or justify her feelings, her intolerable bigotry, I cannot. Might I be able to put her beliefs in a social context of a time, maybe, but I won’t. While she might have been likeable in many ways, she was intolerant to individuals whose skin was not like her own.

When we dive into our own experiences, we must put those experiences in context of relationships. We cannot give platitudes but do necessitate a degree of respect and understanding that every memory isn’t the same as what might have happened. There is always a bit of light fog, something hardly perceptible, amiss in what we remember or even experience at the moment.

We come to this screen and (hopefully) by now with guidelines to the preconceived notions about our own prejudice. How might we be using that as a crutch, unwillingly or not, to separate ourselves from and in so many ways from the unfairness we treat one another. We can do better. We must do better.

February 2 - Chapter IV. Sin (42 pages)

In this chapter, Sin, Berry advises, “I am under constraint her to use “sin” as a necessary term, but am not using it in its traditional sense … I am using it now to denote a wrong or a perceived wrong …” Sin is charged chapter—greed, a proxy to kill, and how we violate by our silence.

Share Your Thoughts

Reading Berry is to understand he values community. Please share your thoughts in the comment section and we can have a community conversation.

Don’t know what to type? How about what you liked about this third chapter or what frustrated you. Share a quote that resonates. Maybe something you have learned or any of the principals Berry touches upon. Other possible questions are below.

References

We are reading Wendell Berry’s, The Need to Be Whole: Patriotism and the History of Prejudice. Shoemaker & Company, 2022.

The title of chapter III, "Degrees of Prejudice", resonates with me. For ten years I served as executive director of a community-based non-profit organization that addressed issues of homelessness and hunger. African-Americans comprised about eighty per-cent of the people we served. I was confronted daily with the underlying issues of prejudice and racism that helped create and continues to exacerbate the problem. When I accepted the position I considered myself an enlightened non-racist. Almost immediately that self-image was called into question by both clients and people of color who supported the work of our agency. I was shocked the first time a client called me a racist. Although none of the board members ever used the word “racist” one woman, who was to become a trusted voice, called me out for prejudicial statements. Another woman was less charitable when she suggested that I “take my white missionary mindset and go home.” Needless to say, I quickly discovered I had a lot to learn from the people I served and as well as those who supported and challenged me along the way. Yet, as I learned more about my own prejudices, I was also being confronted with more blatant forms of prejudice and overt racism in the white community. Before the days of wokeness, I was called a do-gooder and bleeding-heart liberal, even half-jokingly by some friends. So yes, there are degrees of race prejudice. I see it in myself and I have seen it and continue to see it in the people I have encountered along the way.

Like Mary Beth, I would like to submit 2 hearts, one for each essay this week. Dudley, you humanized the concepts in this chapter and made them understandable and relatable. Perhaps you should write your own version of A Need to be Whole. I think it would be a pleasure to read.

Stacy, I enjoyed your vignette about your grandmother and your admission that you're unwilling to excuse her behavior. There's a connection to the Forgiveness chapter coming in a couple of weeks.