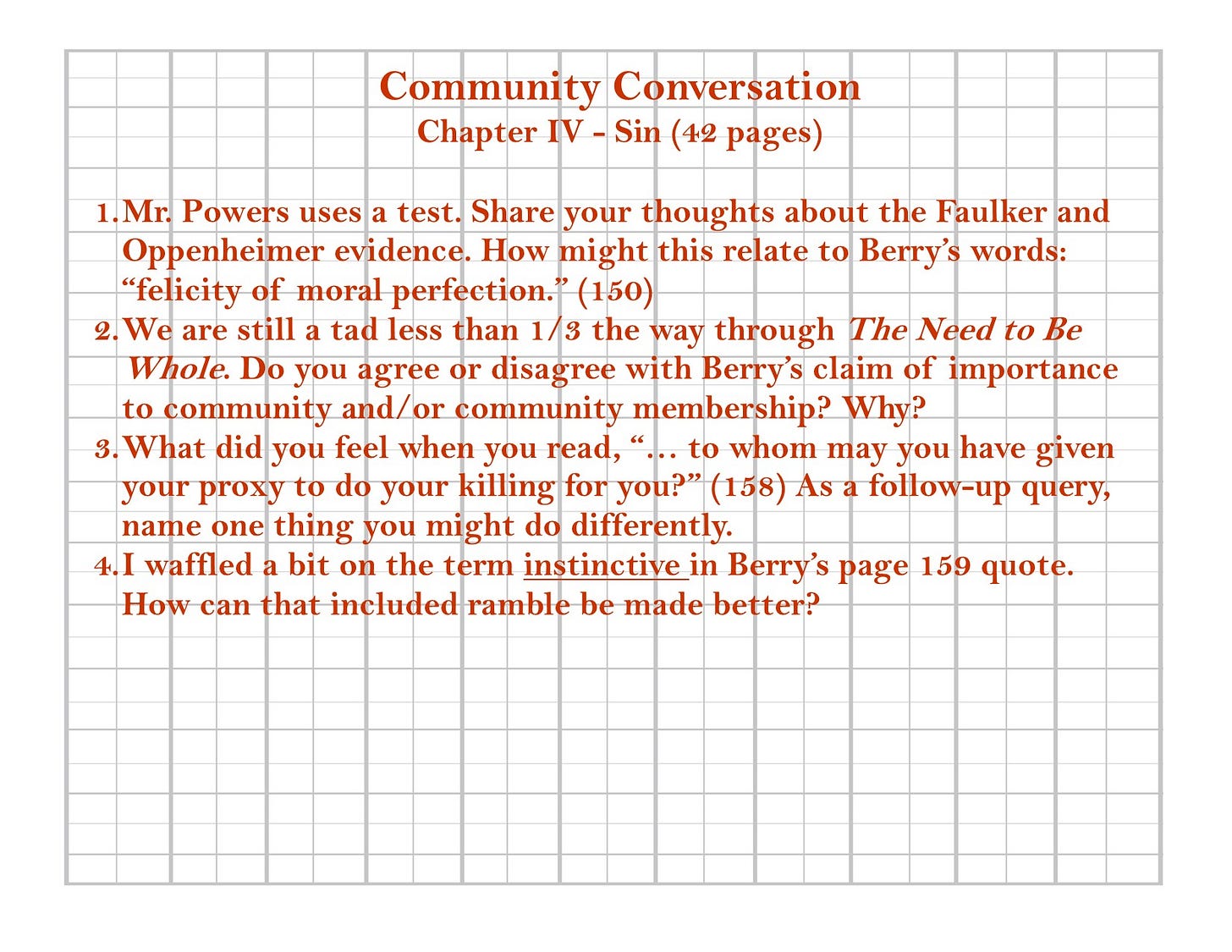

Chapter IV - The Need to Be Whole

Wendell Berry writes about the formation of character, a proxy to kill, and to violate by silence

This is the fourth discussion entry into Wendell Berry’s, The Need to Be Whole: Patriotism and the History of Prejudice.

Share your comments below—this is intended to be a community conversation.

Before this essay forges ahead, it might be relevant to know that my religious foundation is not from a biblical book, especially one that has over 60 English versions. Also, I know that Berry’s Christian belief system is ample in practice and in a dogged pursuit of message sharing in his writing. Still, I never find him preachy, yet I felt a profound dread to write anything on a chapter entitled, “Sin.” Seems that others have similar worries—the stridulation sound of crickets as a night cools resounds with the ten people I ask to write about this chapter.

Chapter IV. Sin (42 pages)

Formation of Character

I think it is best to begin right here:

… there is no effective way for anybody to deal with anybody else’s private behavior. (134)

Berry is nothing if not consistent. I guess by this point of The Need to Be Whole, if the reader has not globbed onto the value of community, then Berry’s arguments fall as pointless.

… because neighborliness is so much a concern of this book. (159)

Does it require a village to raise a child or a community to support a family? What if we are older and widowed, where are the helping hands of neighborhood. If the house burns to the ground, starting over is easier with community. These are not Berry’s examples. I simply want to simplify the conversation—if there is no one else around, you can do whatever you want, but when there are others, behavior is either acceptable, or not. Yet, Berry uses “need” and “required” as a part of his text on “living a shared life” and a “wholeness of heart.”

As a guide I would often ask workshop participants how to define ethic. The answer I never had shared with me, the one I always offered, was/is, “What you do when no one is watching.” I am wondering a bit if I need to modify my go to example, and the conversation in general, after reading this chapter.

To remain true to the context of Berry’s argument:

In more settled times and places, most people lived their private lives, only intermittently public, within and under the influence of the families and communities that formed their characters when they were children. (135)

The formation of character sits with me. What forms character? What guides and motivates and does/how does that evolve or even shift depending on later life experiences and influences? These are (mostly) rhetorical queries with an acknowledgement, on my part, that there is bad that is just bad, and good that gurgles to the top even with those treated badly. Maybe good character longevity, despite the bad, stems from upbringing.

Berry’s religious foundation petitions he list and discuss the Ten Commandments. He favors supportive scripture to guide his rationale. One way that the text is more manageable is Berry’s willingness to frame “sin” into a conversation that is not universally biblical.

I am under constraint here to use “sin” as a necessary term, but I am not using it in its traditional sense as an act or thought that divides us from God or our neighbors. I am using it now to denote a wrong or a perceived wrong that is opposed with the zeal and the personal and public vindictiveness with which religious heresies once were opposed. (148)

With these penned words, Berry wipes the slate chalkboard. It is now smudge free, as it were, and as readers we can choose what marks to leave behind. In a sense, I feel Berry feels a,

… happiness of knowing that one has done the right thing … (146)

Berry presents an idea that the consequence of sin is a degree of loneliness. A possible tool of measurement being that individuals “recognize sinners less by their sins than by our own.” (158)

What a powerful concept to pause with—to validate or invalidate our own actions by the actions we see around us. And from here, from this single idea I can see how we diminish behavior, that behavior which we might have learned with the family and the community to which we were born and mimicked as a part of practice. The space where we formed our values, what it is that we would stand upon. As we surround ourselves with a more debased acceptance of behavior, might we too begin to practice the same or at the very least find ourselves, and others, less accountable for what we might have once considered unacceptable? What is necessary to reform these declining implications, the structure of familiar and community values that reinforce a place to go/to be and thereby less loneliness, a resultant from a different acting out of behavior. In its most distilled simplicity (remember, neighborliness is a cornerstone of this book)—there are behaviors not acceptable at home, not in the community, and transgressions are forgiven for the benefit of community and the recognition that everyone sins, but offenses are met with community consequences.

Though it feels true, I have tired of the generalized phrase, or its similar, that the world is so divisive. This is an excuse to the failure to check our own hate and prejudice and bad doings and instead blame because of our sanitized interpretation and perception.

Deep in the trench of this chapter is an individual’s own elevated morality and precise understanding of what is right or wrong. Couple this with a failed judgement of one’s own sins in the same context. I feel as if I can write an entire long-version research critique on this single idea but there are additional linking components within this chapter and it would be irresponsible for me to let those pass without at least a fleeting word, a daisy chain connecting.

A proxy to kill

First, read and get comfortable with,

… to whom may you have given your proxy to do your killing for you? Or if you think you have no prejudice, can you remember that other people's memories of you might be truer than your own? (158)

Next,

We define ourselves as human only in the weakest sense of that term by our inclination to call wrong only when we can attach them to other people. (172)

I think Berry is wrong when he says,

The wasters of the world do not derive their abuses from any “text,” but rather from their instinctive greed and the capacities of their technology. (159)

Honestly, it is the rosy outlook part of me that takes exception to the term instinctive. To gather my argument, I referred to Merriam which defines with words like impulse, below the conscious level, spontaneous, or response. As I reevaluate the term, maybe instinctive does work—as in greed of the moment and the inability to see outside of oneself and to not be able to self-define right or wrong or be unwilling and incapable of this definition because those around you are doing the same. Which means, bad behavior breeds (might) bad behavior which says even more about those who adhere to a stronger ethic of acceptable behavior.

Acceptable as in do wrong but it isn’t’ really wrong because we all do it; or

Acceptable because there is no pushback to establish a moving boundary of bad behavior toward deplorable.

In these essays I often fall into an idea to oversimplify my arguments. I focus on using that which I am willing to always discuss, the environment. I believe that we are willing to waste and pollute because we know nothing else as an economic motive. That hands have grown too clean by avoiding soil and building a mutually beneficial relationship that comes with a nature-based relationship. I grow exasperated with an overbroad assumption that we cannot reform actions that are for the “community” and for a greater good.

Though it clearly is destroying both our land and our people, we don't notice it because all of us are guilty of it, whether directly or by proxies given to other people to be greedy on our behalf, and our guilt looks merely normal. (168)

Living in a rural community with my greatest responsibilities being to manage a small homestead, I wonder how many people truly evaluate what their impact is from the food purchased at the grocery, the gas their vehicle guzzles, the charge of electricity to light up multiple rooms in the house, or in the investment in the stocks, mutual funds, and credit card banks that support pillage. I also try not to beat the bush too much about the ongoing conversation making the world a human-centered place. Berry tells us,

To think of the world as human-centered is both a blasphemy and an ecological absurdity. (163)

If this sentence did not stop your reading in its tracks, I might have to argue you are not reading closely enough. I admittedly take great solace in the idea that mother nature will win, and I hope she wins sooner versus later. I do what I can, but I am, too, guilty. I have assigned my acceptance, a tacit approval on how and where I spend my money, where I compromise, and anytime I toss something into the trash. Sometimes, I understand why bad actions is an acceptable norm. My good efforts feel so inconsequential yet never far out of reach is the thought, and what spurs me into action is:

How can we love our neighbors by abusing or destroying the watershed or the ecosystem or the ecosphere on which we and they mutually depend? (159)

Well, how do we?

We violate by our silence

Part of why I've been so adamant to read the text of The Need to Be Whole publicly, as it were, with my own essays is to hold myself accountable for at least trying to share a larger message (my assumption being that Berry was not going to steer me in an unexpected direction). While conceding that we so often read what supports our own world-making. Already, I have been enlightened with a measured instruction to scrutinize my own prejudices, and to avoid generalizations when specifics are better at articulating a message. Likewise, I expect when I read Berry to continue my dedication to being a better steward of the land.

Some find it easier to articulate there are few existing social and environmental problems and to prejudice that with race, class, gender, etc. An arm’s length stance to inequities—here is a good place to insert segregated schools, red-lining, food deserts, but I must assume for this limited writing space you know these problems. Nevertheless, (says Pollyanna) we live in a time where change can be made to happen with enough voices and showing up in the places where change can be affected—community meetings, school board discussions, library forums. The loudest voices, it always seems get the most attention, sometimes for selfless reasons, sometimes for selfish reasons. Push-pull, this is what happens in community conversations.

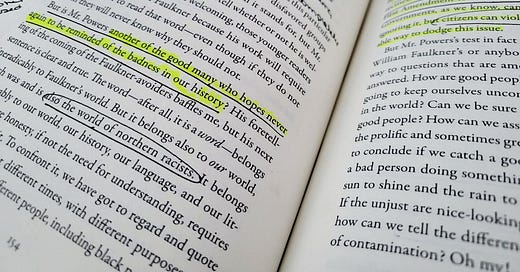

In the quote that follows, Berry is talking about confrontation when he writes of Faulkner and Oppenheimer. Also, about eradication of memory and avoidance. The quote refers directly to Nigger Jim.1 Blanch. Feel uncomfortable about our history, because if Mark Twain’s Huckleberry Finn is to be banned because Nigger Jim offends our sensibilities where is the much-needed conversation to, as Berry tells us in Chapter I, “…all that we hold dear depends upon our determination to hold ourselves as equal to one another.” (17) Then in Chapter II, “Without a sustained movement of conversation back and forth between the public and personal, the general and the particular, Equality and Justice decline toward nonsense … (3). Or finally in Chapter IV, “… by listening and remembering …” (141) instead of being “another of the good many who hopes to never again be reminded of the badness of our history?” (154)

To be afraid to do this in a public classroom is to make a political correctness a form of public censorship denying the protection of the First Amendment to Mark Twain and of course to other writers. Governments, as we know, can violate the First Amendment by ignoring it, but citizens can violate it by silence. There is no honorable way to dodge this issue. (155)

We should not continue to avoid our history, nor our present. Our participation in the present does not validate avoidance as excusable. Doing so, of course understanding the definition and context of our own rights and wrongs, formulated as well with our willingness to use specifics or generalizations, is simply avoiding the confrontation and acknowledging the truth.

February 9 - Chapter V. Forgiveness (72 pages)

Forgiveness, what might that mean through the eyes of Berry. The chapter feels slow and calm, like the act that forgiveness might require. Plus, there is mare with testicles.

Share Your Thoughts

Reading Berry is to understand he values community. Please share your thoughts in the comment section and we can have a community conversation.

Don’t know what to type? How about what you liked about this fourth chapter or what frustrated you. Share a quote that resonates. Maybe something you have learned or any of the principals Berry touches upon. Other possible questions are below.

References

We are reading Wendell Berry’s, The Need to Be Whole: Patriotism and the History of Prejudice. Shoemaker & Company, 2022.

I am grappling with a way to summarize the concept of sin and its corollary, finger-pointing. As I understand his argument, sins are those actions by which we do genuine harm to the community in failing to hold ourselves accountable to ourselves and to each other. Actions which simply demonize other peoples or are destructive to the land are not sins but convenient excuses for dividing and conquering. Such actions are dangerous but disposable or reconfigurable according to one's perceived needs.

"Thou shalt not steal" is a proscription against a genuine sin, that of Avarice or "Father Greed," which is the motivating factor that allows a greedy person to blame others according to whim, thereby setting up a chain reaction of public blaming and identifying as "sins" things that are hindrances to or offenses against one's personal sensibilities.

I love the poem "Questionnaire" which it so nicely sums up the ways in which we excuse the actions we take when push comes to shove and convenience gets in the way of principles, or when as Stacy indicates, we seem to be left with no other option other than to go with the flow. Berry concludes by writing "much more is expected of us, and needed from us, than what may satisfy the wishes and perceived needs of individuals and of groups divided by racial, political, sexual, or other differences." (p. 171)

The best comment I can make on this chapter is to post Berry's poem "Questionnaire."

Questionnaire

Wendell Berry

1. How much poison are you willing

to eat for the success of the free

market and global trade? Please

name your preferred poisons.

2. For the sake of goodness, how much

evil are you willing to do?

Fill in the following blanks

with the names of your favorite

evils and acts of hatred.

3. What sacrifices are you prepared

to make for culture and civilization?

Please list the monuments, shrines,

and works of art you would

most willingly destroy.

4. In the name of patriotism and

the flag, how much of our beloved

land are you willing to desecrate?

List in the following spaces

the mountains, rivers, towns, farms

you could most readily do without.

5. State briefly the ideas, ideals, or hopes,

the energy sources, the kinds of security,

for which you would kill a child.

Name, please, the children whom

you would be willing to kill.

Wendell Berry. Leavings: Poems (Kindle Location 51). Kindle Edition.

I must admit this poem and this chapter challenge me and my way of life. I am much to comfortable relying upon the sins of others to feed, clothe, house and fuel my lifestyle.

Regarding Berry's critique of Tom Friedman's hopeful defense of "green greed" to save us from ourselves, he writes (later in this book or in other writings) more at length about the merchants of technology creating and selling "fixes' for problems technology created. i.e. ways to repair the top soil that has been depleted by technological advances in factory farming.