Chapter VIII, Part 2 - The Need to Be Whole

Wendell Berry's agrarian theme continues and there is a consideration of: good, beautiful, sound, useful, and pretty.

THIS POST MIGHT appear clipped or truncated in your email. Click View Entire Email to finish reading.

This is the eighth discussion entry into Wendell Berry’s, The Need to Be Whole: Patriotism and the History of Prejudice.

This week there are two essays. The first from Jody, the second from Mary Beth.

Share your comments below—this is intended to be a community conversation.

I met Jody 25 years ago on a work project in Virginia. As I remember, she was the first female I’d ever met who was unafraid of backcountry tools, genuine hard work, and sharing that passion with others.

Jody Bickel is a self-described writer, rambler and renaissance woman. Her intertwined ventures and adventures have allowed her to peer into rural and wild places around the world. She advises leaders and their respective institutions and enterprises on how to drive system change for the betterment of our environment. The rhythmic cadence of walking more than 8,000 miles through working and conserved lands restores her. In return, she labors to inspire resiliency for people and place. Her writing blends themes of home, stewardship, labor, agriculture, community, nourishment and our natural world.

Readers have been introduced to Mary Beth, the writer behind Sea Cow. If you want a bit more lighthearted read, swim into her weekly series on tides.

Chapter VIII. Work (66 pages) - the last eight essays

Jody’s Essay

I’ll begin by acknowledging that there is much to consider in the entirety of this tome. There is a wide, varied and stern butterfly netting process that occurs in Mr. Berry’s construction of his logic chain. Some links may offer more clarity than others. Certain of his links may rankle or intone strong feelings for the reader. A portion of links may be grasping attempts or areas in which the reader has little to no familiarity with as they follow his lead. Regardless of resonance, I commend his efforts rather than wallow in their imperfect-ness – all from my singular life lens.

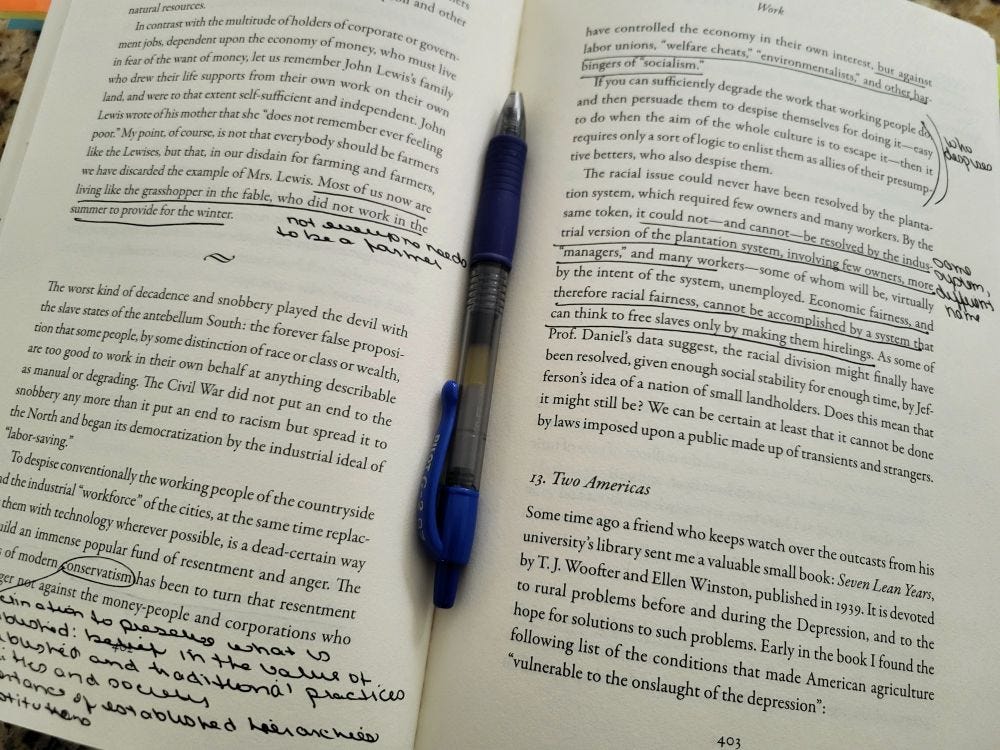

My view is that Chapter 8 Sections 10-17 is the very crescendo of Mr. Berry’s labors on this matter. It is here and captured fully within the two quiet pages of Section 17 entitled Goodness, where courtesy of his pained efforts, we can look backward and forward simultaneously to “see what we don’t see” (321) - recall Johnny Paul’s words. It is this seeing that wholly horrifies me.

Our language speaks in many tongues, but we hear so little of it and fail to “see” its transmogrification. A silo is a tower on a farm used to store grain. To silo is to isolate. Environment is characterized as the natural world, as a whole or in a particular geographical area, especially as affected by human activity. Now we talk about “our environment” in ways often having nothing to do with nature. Season used to refer to the four divisions of the year or the process of adding spices to our foods. Now we use it for taxes, holidays and television programming. I’ve seen the incremental shift of farming to production and farmers to producers. All people who eat and buy are consumers. Living a “hand to mouth” existence of growing to eating fully by our own direct labor has now morphed into slogging in hated wage work for a dollar to buy cheap food from someone and somewhere else’s subsidy and praying to make it to the next paycheck. We operate in a consumptive world of natural resources and human resources. Pay attention! This should horrify you.

I’m not much into dystopian storying but two references strongly come to mind here. The first is the 1973 film Soylent Green which forecasts the cumulative effects of environmental polycrisis that results in people literally consuming themselves via a food-like product for and of the masses. As I researched, I was aghast to see that there is a real-life Soylent Green vegan protein bar available for online purchase. I was reminded of the second reference as Berry writes:

It [the nation and the country] will treat its own country as a foreign land, a Third World to be colonized and plundered. (443)

Stranger in a Strange Land, is a 1961 novel by Robert A. Heinlein. The title is a variant of this statement in the King James Bible:

Zipporah gave birth to a son, and Moses named him Gershom, saying, 'I have become a foreigner in a foreign land'. (Exodus 2.22)

This socially complex novel is the story of a Mars-raised human arriving to planet Earth and profiles “his interaction with and eventual transformation of Terran culture.”

Berry’s laborious and lumbering logic chain, as I see it, looks somewhat like this.

Pre-judgement in any form is of little and often backwards value » People and their community are integral and interdependent on nature and home » How we go about work and education have far-reaching effects on us as individuals and in community » This then translates into creeping little pivots of how we relate to place, love and nourishment » When we are separated, isolated, siloed from each other and our direct sustenance, the consequences include polarization through politics, economy and numerous other seemingly harmless wedges » As chattel zombies we turn in servitude to the institutional bureaucracies that we once formed to conveniently service our distaste for the hard work of being a responsible two-legged species.

“It” writes Berry,

Will unknowingly subsidize its ‘cheap food’ and ‘cheap energy’ by the ruin of the land and the land’s people. (443)

“It” can be likened to Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein in which the monster we created eventually kills us.

It's horrifying to see this. Going along to get along means more of the same. While some won’t get it and some don’t want it to be got, this is what Mr. Berry has worked so diligently at unearthing on our behalf and because he was so fully compelled to. Truth. I wholeheartedly respect him for this. But gulp…in the knowing…what to now do? My life experience has taught me that people are generally and highly resistant to change when it’s in front of their faces. Sadly however, the creeping, sneaking, eroding change that comes from behind, just a little here and there and deceivingly presenting itself as not really anyone’s responsibility—this is the evil that threatens our very existence.

I’d like to fantasize that it’s as blessedly simple as Alice awakening from her Wonderland dreams, but I love the truth much more than the lies. Seeing now and going forward is no easy path. It won’t be easy if we settle more deeply into our modern machinations of slavery and prejudice. And it won’t be easy if we subvert the dominant paradigm—as a person in a place and a community. There is no easy life. There has never been an easy existence even if you didn’t even know what you never did see.

I wonder how dear Mr. Berry feels at the process and outcome of this particular work of his own life. This may be his absolute and sharpest clarion call for truth in these matters. If it were me, I think that I would go and sit for a while in a field in the sun to gather myself as fully as possible. Then, as I do now, I get up and go onward into the fog to see what I can see.

Definitions are from the Oxford Dictionary

Mary Beth’s Essay - Husbandry and Me

Mary Beth listened to The Need to Be Whole as an audio book. As such, there are no page number quotations in her essay unless I could find them easily.

Any trans farmer would justifiably be repelled from this book by Berry’s bigoted comment on pronouns in Chapter VIII Section 15, rather than feel supported in their small farm endeavors. An organic vegetable farmer might toss the book aside upon reaching the quote in the same section deeming their work a “distraction,” and “too small to be ecologically significant.” Wendell, help me out, small farming good, but too-small farming bad? Alienating his potential audience left and right, I have my doubts that he is the right ambassador for advancing thought on the impacts of race prejudice in agriculture.

That said, there is something encouraging about a narrow band of diehard Berry fans finishing the book and coming together week after week in a community discussion. Berry hasn’t seen past some of his biases, but none of us have. Hopefully, together, we are seeing farther and with clearer sight than when we started.

Back in Chapter III, I made a comment focused on numbers of farms, the way 600 family farms can be wiped out by one gigantic, awful behemoth of a farm of 30,000 cows. I am never more on the same wavelength with Wendell Berry than when he approves of a farm where “Each of the cows was known by looks, behavior, and name.” (52)

“Who can know a thousand cows?” (53) was the most heartbreaking line in that chapter. Nobody knows a thousand cows.

I’m bringing this earlier quote forward because the latter half of VIII Work revisits the grief over lost small farms, and the particular knowledge, muscle memory, and skillsets that are lost each time a farmer loses or leaves a farm. This body of knowledge, collectively known as husbandry, is the work most devalued and depreciated by the Calhounian division discussed earlier in the chapter. It is work that is best learned through doing, through watching and working alongside someone with the know-how already embedded in their bodies.

When such a culture dies, it is not only dead, it is gone. And so the loss of the cultures of husbandry, incomplete or inadequate as they often were, is not a matter only of history or sentiment. Husbandry is the discipline of thrift and thriving, of fruitfulness and frugality, of care and caretaking, and taking care. (397)

Husbandry is a major component of my occupation as a fish biologist. Growing up as a farm laborer prepared me for this work at least equally as well as my college education. The same muscle groups that grew ropey in my arms as I hauled pails of milk to the calf pen are in use today as I haul buckets of seawater. When I prepare diets for the fish in my care, I experience frequent sense memory of feed stores and granaries. I mark the seasonal changes in fish appetites, know their reproductive cycles and the physical actions I must do to enable their development from embryo through adulthood. I attend to the ending of their lives with utmost attention to the alleviation of suffering. If I replace the word “fish” with “cow” in this paragraph, this is a paragraph about farming.

The work I do makes scientific research possible; it does not feed the world directly, but instead, aims to learn how to sustainably feed the world from our wild oceans. Along this career path, there are ranks and pay scales that value certain work over other work. I do the lower value work, the husbandry. It is not considered as prestigious nor compensated as highly as those whose work is to write research papers and run analyses at a desk. But there would be nothing for them to write about if no one did the labor to keep the animals alive.

In dairy farming, the kind where each cow is known, farms after WWII could make a living because the government set the milk price. But that only worked as long as production held steady and did not overmatch demand. Production instead increased because farmers wanted to make a little better living, but the price dropped in response, so farmers, instead of making their same living, struggled to make ends meet at all. Then by trying to reduce production, incentivizing the destruction of cows, the cessation of production for a period of years, it was hoped that a livable price to farmers could be supported, but the program was more successful in its destructions than at stabilizing the price received by farmers for their work. Embedded in this chapter’s Section 13 “Two Americas” or what I’d nickname “the Krugman rant,” is what Berry accuses PK of missing:

… how a population of farmers might be affected by being forced to buy on a “free market” controlled by the sellers, and to sell on a “"free market” controlled by the buyers. (413)

If you control the price and control the supply, the consumer experiences the convincing illusion of uninterrupted cheap milk in the grocery store. The consumer may forget about cows, forget about how milk is obtained, forget the work required, forget that land and land stewardship is necessary for milk to appear in their shopping cart. All that matters is the milk’s constant availability and cheap price. Berry speaks of this forgetfulness:

It [the nation] has forgotten, so far as it ever knew, the kind and quality of the work that is required for the good health and long life of the economic landscapes and their human inhabitants. It will not, because it cannot, imagine that such work can be highly skilled, loving, pleasing, and continuously living in the home places of the earth, work that is beautiful in the doing and in the results. The nation will not support such work, or pay for it. Its unconsciousness will lie over the land like a cloud. It will unknowingly subsidize its cheap food and cheap energy by the ruin of the land and the land’s people.

Once upon a time, people lived on the land and knew how to do the work of the land, and bring forth all they needed to feed themselves from the land. Now, consumers can “feed themselves” only because so far, the shaky supports propping up a bad system haven’t yet snapped. When they do, the illusion will evaporate, and the nation will starve. But it won’t be because Berry hasn’t done his part to explain the concept to us throughout his prolific and devoted career.

March 9 - Chapter IX. Words (40 pages)

This will be the final chapter of The Need to Be Whole, an accounting that as individuals we cannot be whole alone, the implication of no permanence, and violence as a way of life. And then there is glyphosate - as in your cereal.

Share Your Thoughts

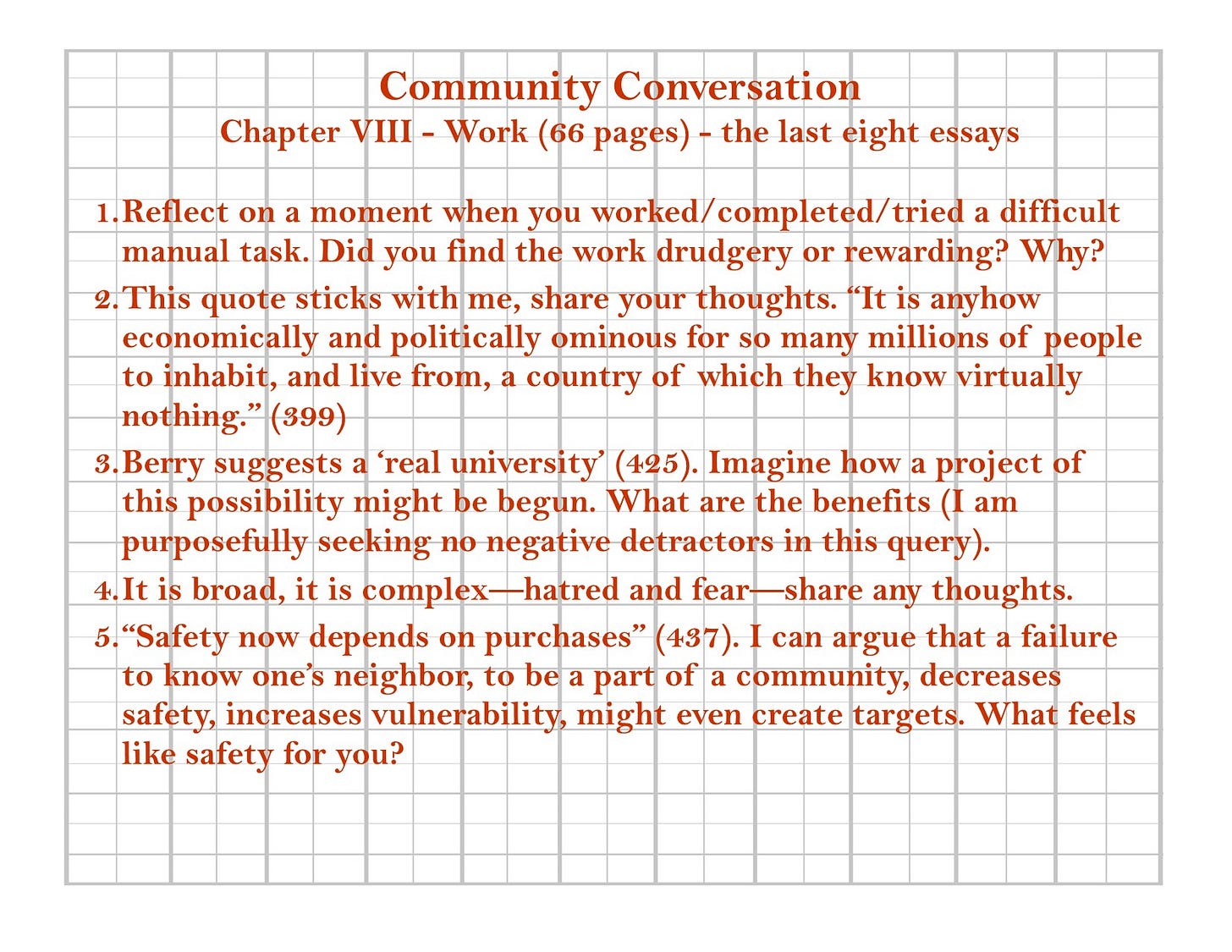

Reading Berry is to understand he values community. Please share your thoughts in the comment section and we can have a community conversation.

Don’t know what to type? How about what you liked about these last eight essays of the eighth chapter or what frustrated you. Share a quote that resonates. Maybe something you have learned or any of the principals Berry touches upon. Other possible questions are below.

References

We are reading Wendell Berry’s, The Need to Be Whole: Patriotism and the History of Prejudice. Shoemaker & Company, 2022.

I am hard put to come to grips with Chapter VIII just because it is so long, and I appreciate Mary Beth's and Jody's essays this week for having done just that. As Jody says, this is the crescendo of Berry's labors in the book. For me, this is where he brings the past into the present, and in Section 9, "Land Need and Good Work,' clarifies what agrarianism is and is not. It is not sentimental or nostalgic. Indeed, nothing that requires such constant attention and hard work while at the same time being so satisfying, could possibly be nostalgic. He writes, "As I understand it, agrarianism, unlike industrialism, recognizes and accepts absolutely the dependence of the human economy--like human life, like all life--upon the natural world." (p.363)

This is followed a few pages later by a short take on the term "barbarians" whose multi-faceted ways of providing sustenance were deprecated by city-state bean counters. (p. 370 ff.) Millennia later, the ability to provide for one's family in a community of neighbors is still being looked down on and legislated against.

Speaking again as a Kentuckian, I appreciated his description of the drive from Shelbyville (rolling hills, excellent farmland) to Port Royal (more hilly and a lot wetter, criss-crossed by creeks). It was a similar drive from Lexington in the Bluegrass country where I grew up, to Mason County on the Ohio River where my grandfather farmed tobacco and raised cattle. I had never really thought of the geological underpinnings in quite that way, but we cannot escape the fact that where we live determines our lives in countless ways.

Wonderful, Jody, happy to share this space with you today, and thank you to Stacy for arranging and coordinating and annotating my pages and correcting my quotes (and, and, and! You're a queen.). I agree the book crescendos to this section. I bow to Jody's diagram of the "laborious and lumbering logic chain" oh what a perfect description, said with admiration I know, but also, calling it what it is.