Chapter VIII - The Need to Be Whole

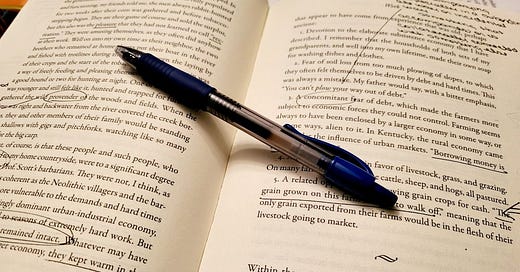

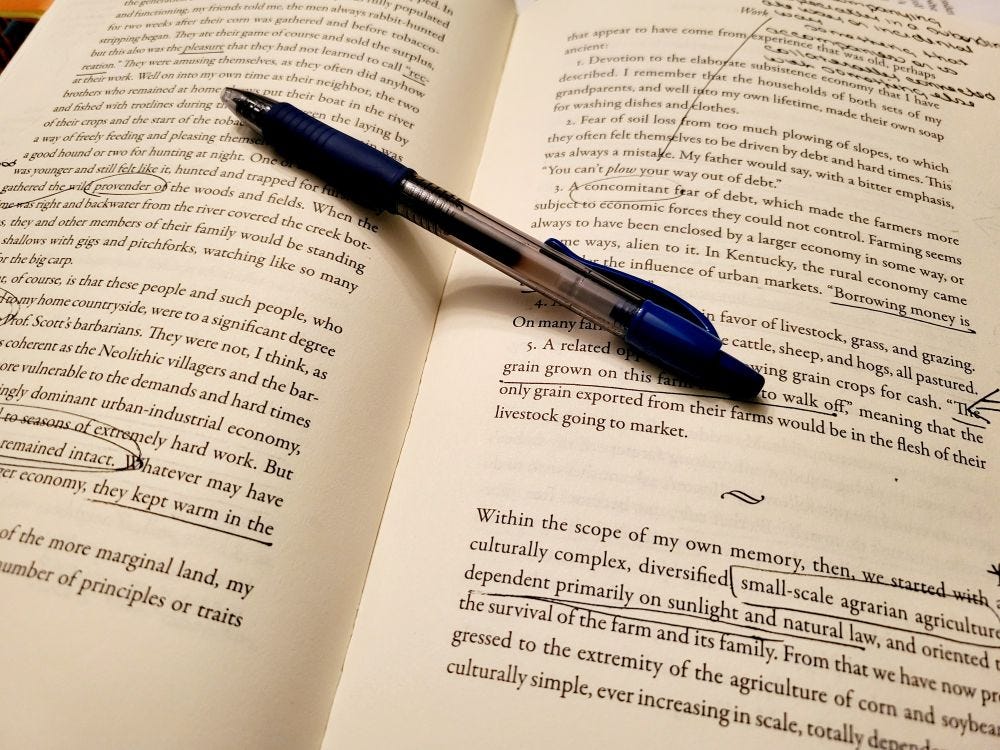

a small agrarian sampler from Wendell Berry - proof of life, to sell the ancestral home, work as an honest thing

This is the seventh discussion entry into Wendell Berry’s, The Need to Be Whole: Patriotism and the History of Prejudice.

This week there are two essays. The first from Mary Beth, the second from Stacy.

Share your comments below—this is intended to be a community conversation.

📖 Continue reading - Chapter VIII, part 2, responsive essays.

Mary Beth is the amazing writer behind Sea Cow. She is a writer who encourages me to be better, and for that I am most grateful. Here is what her Substack is about.

Sea cows belong to the Sirenians, named for the mythological seabird-women who bewitched sailors with song. I’m drawn to sirens, selkies, and the goddess Io who swam the seas in the form of a cow. Most of my writing is about women, whales, and cows. Most of it takes place in the two landscapes that form the hemispheres of my soul: the dairy farm where I grew up, and the ocean I live alongside.

Mary Beth Rew Hicks is a marine biologist and writer on the Oregon coast. She is writing a memoir about women and whales. Her writing has been published in Selkie and Assignment.

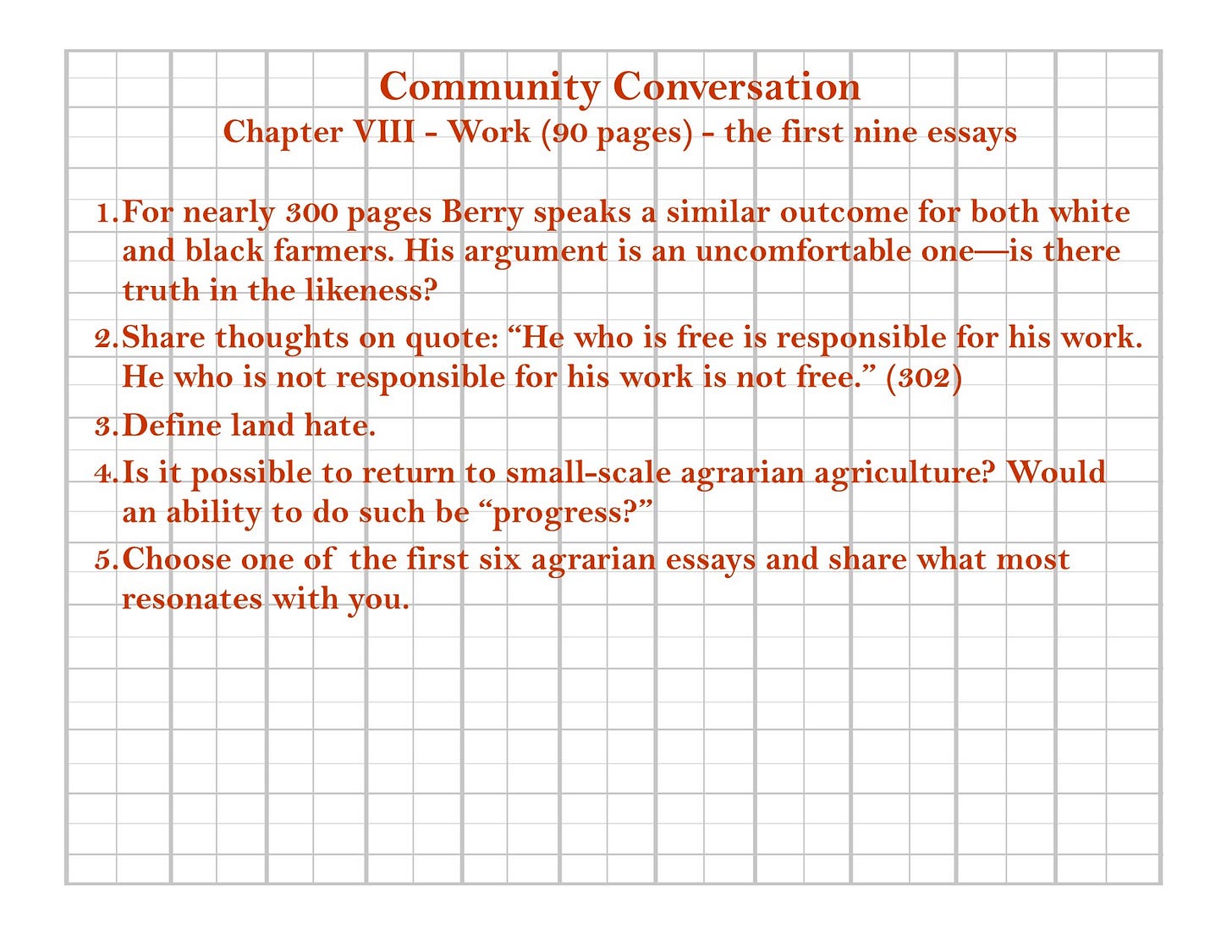

Chapter VIII. Work (90 pages) - the first nine essays

Mary Beth’s Essay

Mary Beth listened to The Need to Be Whole as an audio book. As such, there are no page number quotations in her essay.

If you’ve been subjected to any of my comments on Stacy’s essays on the book prior to today, you’ve noticed I have a hot and cold relationship with this book. I often have that kind of relationship with older men whom I admire, but who infuriate me with not being very good feminists. Like my dad, Edward Abbey, and Joseph Campbell. I chose to focus on the “Work” chapter because I believed it was where Berry and I would most align. I did stop talking back as much when I arrived at this chapter, though not completely.

In “Land Greed and Land Need,” Berry shares his admiration for our sixth president John Quincy Adams; a man who opposed slavery and believed in the “sanctity of treaties.” I began to nod along, until Berry claimed those of us who appreciate political correctness would dismiss JQA’s words because of his use of the word “savages.” In fact, I am the one feeling dismissed here, and I think Berry did more damage than good during each of his rants against PC which recur in the chapter. Indeed, we have anti-PC rhetoric to blame on some level for our current national predicament. Just because I prefer folks to refrain from using slurs and name-calling to make their points, doesn’t mean I can’t appreciate a long-ago president’s journal entries within their historical context. I find Berry’s point that “the north was not the citadel of virtue” quite compelling, despite my annoyance with his delivery.

Then Berry delves into an analysis of Work, the ways in which work is perceived, and can be both valued and devalued in ways that affect our wellbeing, our psychology, our connection with the land. Calhoun made a distinction between work that is not degrading and work that is degrading and fit only for slaves. Berry leads us along the chasm that has now grown from that initial racist fork in the road. Workers (of any race) who perceive work as degrading will despise themselves for doing the work, and soon they will “despise the land itself.” The worker will seek to “rise above the work.” Berry paints with broad strokes, deciding that to be dependent on the work of others is a form of slavery; that being “captives of the labor market” is a form of slavery; that there is “slavishness inherent in industrial work,” and that “we have enslaved the water, the air, the ground.” I do not believe it is useful to liken so many things to slavery that are not slavery. But I see his line of reasoning regarding ways we are impoverished by the perpetuation of the Calhounian division.

In “Work in Slavery, Work in Freedom,” Berry discusses the general abhorrence of work and states that “this prejudice is responsible for… the replacement of vocation by job, for labor saving, labor replacement, and so forth.” As we continue to deem certain work degrading, we desire not to do it and thereby become enmeshed in (agri-industrial) systems that further degrade workers and further degrade the land. By example of an alternate view of work, the story of a prisoner in one of Stalin’s work camps illustrates how even someone “living at the limit of human endurance” can be uplifted by his work, can take pride in it and have integrity as a worker.

As Stacy mentioned in her trailer for this week’s portion of the book, we next come to an “agrarian sampler,” and in parts 4, 5, and 6, we learn how several authors have influenced Berry on matters of the Black experience of agrarianism. In the chapter on Nate Shaw, the reflections of a Black farmer recorded by a white professor burst with the tangible, visceral detail of farm life. His character embodies, “Work, pride and competence in work, a proper measure of independence, love for land and creatures, careful husbandry of things in use…pleasure in what he had.” Two fictional accounts of Black agrarianism, written by Black authors, follow. Berry appreciates (as do I) the way language enables us to get away from “loaded abstractions,” that imagination allows us to envision “wholeness as a possibility.”

Following his thoughts on debt as another form of enslavement, we reach what feels to me to be a crux of the book. In “Official Prejudices,” I highlighted an excessive number of passages. With the help of Professor Pete Daniel, Berry enumerates the losses of small farms and farmers from the 1950s onward.

“To a member of a farm community who has been watching and aware for a long time, numbers such as these are not surprising, but a heartbreak adheres to them that does not wear away.”

Berry, via Daniel, investigates the systemic racism that cut Black farmers out with bladelike efficiency. Though Berry acknowledges the loss of Black farms and farmers, he insists we look also at white farms and farmers. “During the period in question, no category of farmers increased or remained stable. All declined, though some declined more than others. The three prejudices, obviously, were these: One, the prejudice against farmers. Two, the prejudice against small farmers. Three, the prejudice against Black farmers, most of whom were small farmers, and who therefore suffered three prejudices.”

I know well the “prejudice against farmers,” as a kid from one of only two dairy farm families in our rural elementary school. We farm kids were the targets of pejoratives like “hick” and jokes about how we smelled. Berry attributes the specific prejudice against small farms to the agricultural policy of the 1960s and 1970s. I have arguments with some of his perceptions and recollections of U.S. Farm Bill policy, but I agree with him that it has meant nothing good for farmers like my dad. Though we can argue when on the timeline the small farms started to be eaten by large ones (earlier than Berry says) and we can point out that the infamous “Get Big or Get Out” is misattributed to the wrong Secretary of Agriculture in this chapter (at least as far as my research goes), we can definitely point to those authors of policy and their gigantic flaws. I liked this article’s succinct history of U.S. Farm Policy. It is quite relevant to the 2025 political moment, in addition to its relevance to our discussion of Berry’s The Need To Be Whole.

One more link I can’t pass up sharing: Once upon a 1977, Berry went toe-to-toe with Earl Butz in a debate. There are reasons I will never give up on my favorite curmudgeon, and this would be one of them.

As for the third prejudice, race prejudice, Berry claims that the worst period of prejudice against Black farmers was during the Civil Rights movement. After reading about the steep decline in Black farmers even in the leadup to World War II, I am not sure of this assertion, but I appreciate Berry’s reasoning about how providing aid to Black small farmers would have required a fundamental change in agricultural policy, something the bureaucrats were unwilling to make.

The agrarian portrait of Work that Berry paints is one that appeals to those of us who have dabbled in growing our own food, packed fruit into canning jars, butchered a chicken, tried our hand at making cheese or soap or quilts, done the work of caring for livestock. To live a life in harmony with the land, obtaining most of one’s needs from the land and taking care of the needs of the land, one must be “reconciled to seasons of extremely hard work,” as Berry says of the farm folk sharing his countryside. It’s not the popular stance in modern society. To embrace it, one must yearn to be, as Berry puts it, “uncaptured.”

Stacy’s Essay

It is in this chapter that I break the spine of my book, grab a second colored pen to highlight more notes, and begin to fold and/or dogear pages. I could write, might write, an entire essay on 9. “Land Need and Good Work.” But not today. Instead, I tap down writing a long essay, and also my desire to speak of literary craft, to instead spend a few moments with “Ernest J. Gaines: The Freeing of Imagination.” Specifically, I want to weave together two ideas—both regarding collective memory, both situated in place, one human, one nature-based.

Do you ever wonder what you will leave behind, and by leave behind I mean the memories others have of who you are, the work shared, a shared trajectory of meaningful recollections that will time and time again be passed to the next generation, the people that never knew you but know of you because the stories continue to be a part of conversation? Remembrances that enact the shake of the head or a small laugh or a slap on the knee?

What is important is that Johnny Paul is an accomplished talker because he is a member of a talking and storytelling community, a community that knows itself and understands itself by listening to its old people tell its stories, and so, by this constant reminding, remembering its history. (331)

I have no children of my own and my legacy dies when my ashes are strewn into the mountains, forgotten as the wind passes and locates the dusty fragments into the accumulated dirt. Will someone remember a story of me—probably not. If any are remembered, it might be those where I share the not-so-secret secrets of the land with those who sought to move past their fear and discomfort to find a wholeness, with outside. Maybe what is remembered is the inspiration and confidence I offered in a land that can feel overwhelming, substantial, and mystifying.

This essay is a reminder of loss, not just of individuals but of a collective memory. When the last old man dies, there no longer exists a recording resiliency to keep the stories alive. This same collective memory can be construed to the wild places we visit. Memory tracks change but individually it is hard to comprehend transformation (both lovely and ugly) with no background. In nature, I think of where tree line has moved upwards, or picas are replaced by chipmunks, or seasonal tarns are empty and tethered only by the rocky boulder bottom.

What does it mean to have knowledge of a people and their place as a community or neighborhood and how is that different from having knowledge of a natural place before its exploitation. Berry says, “superseded people” (319) but superseded people is also superseded land—cast off, replaced, of no value, disposable—and this saddens me. This term folds together so many of the positions Berry has been making for 300 pages. A rootlessness in place and soil is visceral, uncomfortable, and shameful.

In this example, with Johnny Paul speaking.

We stuck together, shared what little we had, and loved and respected each other. (323)

But the summary is simple—in the trees is a cemetery with people who will soon be forgotten. It is the community that maintains a memory where,

The old are stranded, living out their days as leftovers in leftover houses (320)

until someone else can,

… rid all proof that we ever was. (324)

It is in this place, with a measured sadness as the men who hold shotguns, each taking responsibility for a murder. Old men who stand as neighbors to protect not just the graveyard, but the memories, time before the tractor. Hard labor, and reward in the toil, of people who worked the fields and the memories to be collected and memorized until their presence is tilled beneath mechanically induced uniformly shaped rows.

… you don’t see what we don’t see.

…

You don’t even know what I don’t see. (321, my emphasis)

In a chapter devoted so much to work, this example is where a single voice, Johnny Paul, speaks of generations. People who worked the farm, raised the crops, tended the land, nurtured their families, built community, cherished the work and the reward, and buried their kin on the land. Understanding this, Berry thoughtfully considers his note to the reader:

… Johnny Paul is preaching the funeral of a community, in farewell recalling and praising it as it was. He also is including himself among the mourners, and his speech is a lamentation, biblical in its finality and sorrow … (324)

What it feels like to have this remembrance of a people and a place. What it means to understand with a sense of a natural place, to know with a conviction as unexplainable as, you don’t even know what I don’t see.

March 2 - Chapter VIII. Work (66 pages) - the last eight essays

The agrarian theme continues and there is a consideration of: good, beautiful, sound, useful, and pretty.

Share Your Thoughts

Reading Berry is to understand he values community. Please share your thoughts in the comment section and we can have a community conversation.

Don’t know what to type? How about what you liked about these first nine essays of the eighth chapter or what frustrated you. Share a quote that resonates. Maybe something you have learned or any of the principals Berry touches upon. Other possible questions are below.

References

We are reading Wendell Berry’s, The Need to Be Whole: Patriotism and the History of Prejudice. Shoemaker & Company, 2022.

Along with TNTBW, and the reason I am still no further along than the middle of Chapter VIII, is that I am simultaneously reading Coates' "The Message," and a new biography of Harriet Tubman, and "El Paraiso en la otra esquina" ("The Way to Paradise") by Mario Vargas Llosa. This title of this last book refers to a children's game of "Paradise," in which the players go to different places in the yard and the person who's "It" goes from one child to another asking if where they are is paradise. "No ma'am," says the other child, "it's over there in the other corner." Meanwhile the other children keep changing places to confuse the seeker. The relevance here is the subject matter of the book - a contrast between the French painter Paul Gauguin and his grandmother Flora Tristan whom he never knew but who was an advocate for workers' and women's rights in early to mid-nineteenth century France.

For us too Paradise will always be unreachable, which is why I believe it is necessary to understand historical context when weighing up past actions and beliefs in the scales of opinion. Human nature does not change much over time, so whether it's post-revolutionary France or post-Civil War America, or today, the struggles are the same. Race and land use are the salient messages of this particular book by Berry. Knowing the past, what can we do today to make our world on this planet a better place?

Mary Beth, as always, a great essay. Your thoughts always feel to be well formed and considered. Historical context is something I think we often forget. When I consider my grandmother's unacceptable comments about a mixed-race relationship while eating dinner in a restaurant I cringe and find her outburst unacceptable, but I also must be mindful of the historical context of her era and also not being a granddaughter who was privy to the backdrop of her emotion. I appreciate that you mention a need to understand/consider a time - after all, right and wrong is so much the crux of these conversations.

John Quincy Adams is a formidable character. Berry says:

"I know that the gavel or the sword of political correctness will fall upon the word 'Savages,' sentencing Adams to the imperfect and therefore dispensable and forgettable past. But that is only because political correctness has no historical imagination." (293)

Here we have Berry making a generalized statement, something he has been telling the reader not to do for p a g e s. What I admire is that you, and Berry, are making a point of looking backwards to understand the forward of now.

"He was not a perfect man by the measure of his time or ours." (292)

I suspect none of us will be ...