Chapters I and II - The Need to Be Whole

to hold the possibility of better keeping, says Wendell Berry

This is the second discussion entry into Wendell Berry’s, The Need to Be Whole: Patriotism and the History of Prejudice.

Share your comments below—this is intended to be a community conversation.

I sent a note to Mary Beth shortly before I began writing this essay—Berry does two things simultaneously. He clearly states and supports his point while also making it difficult for a general reader to understand.

Without a doubt, I am interrogating the text more so than I would for a book I just want to read, pull a few tidbits and factoids that add to my knowledge. The Need to Be Whole is not an easy read and as such is worthy of critical consideration.

Chapter I. Public Knowledge, Public Language (12 pages)

A mere 12 pages marked with an abundance of ink. When I write the word “possible” in the white space at the end of the chapter, what follows is a list of potential subjects to contemplate to a greater understanding. This chapter has much to rest with but let me try to weave together a perspective.

Actual experience subjects and exposes us to the actual world, in which we must make a living under the obligation to be honest, form opinions under the obligation to be just, and in general suffer the mysteries, obscurities, and complexities that make truth difficult and righteousness imperfect. (18)

The pessimist might want to take exception to the word obligation, particularly as it leads into the action of goodness, but I am not a cynic in this way, so I am going to allow the sentence to stand without argument—for now. While Berry dives into a state of being anonymous and disclaiming an individual personhood, he veers into categories of affiliation which I take to mean that we allot ourselves into a rung of space but not one of actual place.

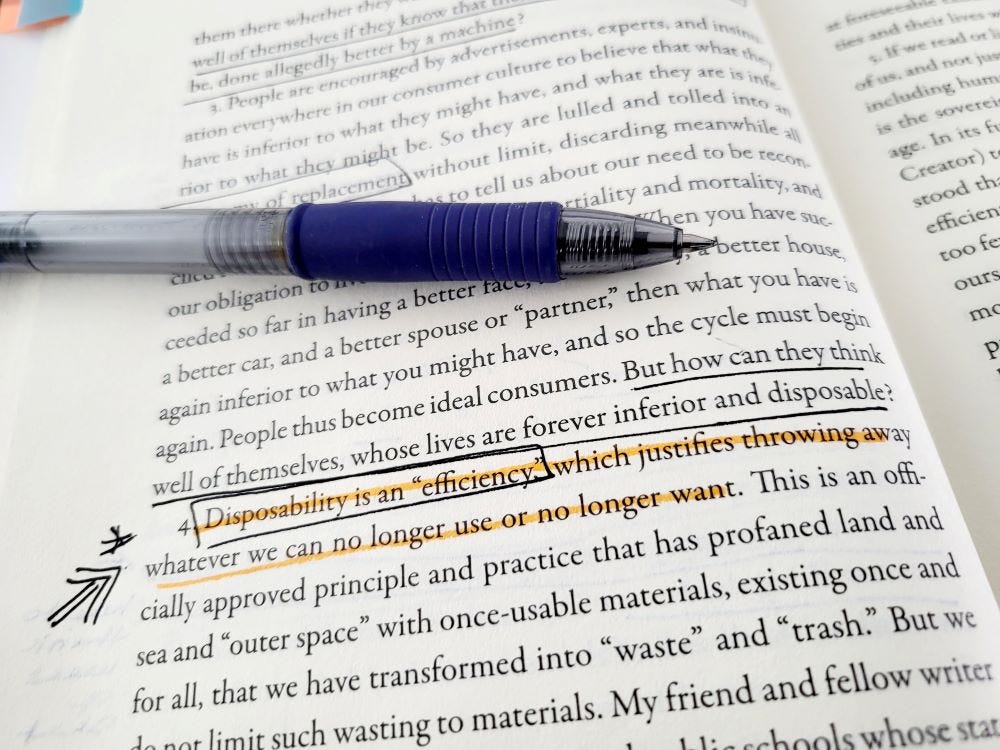

Instead, how about Berry’s use of oversimplification that thrums in the pages that follow. To oversimplify1 as a transitive verb is to: simplify to such an extent as to bring about distortion, misunderstanding, or error and as an intransitive verb is to: engage in undue or extreme simplification.

Is Berry writing with oversimplification as an interpretation in incongruity? Using this theme as the foundation to explain and draw attention to a human practice. Is he being conciliatory in his message or truly trying to illustrate the difficulties of the current livelihood and living?

Exaggeration, Berry says:

is a violence of language, which in politics, is full of the threat of violence of other kinds. Exaggeration—extremities of generalizations, language overpowering knowledge … (20)2

Does this have any relationship value to how to think well of oneself?

Consider what you do for the most hours of your day (if you need a prompt, for many that is working). Is that time of purpose and appreciation or dread and discontent, maybe even resentment? As a guide I cherished my days and nights in the backcountry. It was hard work. I had to be willing to change my hats on the shift of a breeze, but I found true reward in what it meant to introduce individuals to the backcountry in a way that gave outside a physical and emotional significance. It never felt like a job, per se, but a duty in the most satisfying use of the term. Because of my intention to protect the landscape, my desire to bring recognition of wide swaths of land to recreationalists gave my work, meaning. By extension (to oversimplify) the land, my clients, and my job were worthy of protection.

As I consider an unrewarding job, I can understand how it might feel as a grind of:

… longing through their workdays for quitting time, the weekend, vacation, and retirement. (21)

Berry continues this contemplative thought,

They are thus not willingly living, much less enjoying, the most necessary and significant hours of their lives but are wishing them away … How can workers think well of themselves if they do not think well of their work? (21)

When I consider an obligation of truth, I judge the oversimplification in the complexity of purposelessness. The lack of added value and thus the pursuit to identify value and why, often, this comes from belonging to a category when belonging to a familiar community is absent. Being a cog in a wheel that drives someone or something else but does little to provide emotional ambition or drive or aspiration, makes it possible to devalue personal appraisal. Participation is not from desire but from requirement. Each of these things an oversimplification of a perceived belief that not only are human’s disposable, but so is the soil beneath our feet, the air we breathe, and the waterways we rely upon. Personal experience defrauds obligation because we have oversimplified our social view in an exaggerated reliance on categories and, thus, shove aside our individual self-worth, a value once verifiable as an innate part of community.

Chapter II. Equality, Justice, Love (16 pages)

Take just a moment and mentally consider your values.

We need them, that is, as the names of familiar ideas by which to rectify our thoughts and our lives. But we need them also in the particularity of effort as we practice them, or as we try to fail to practice them. (29)

Now ponder for a moment the differential in the two terms: particulars and generalizations.

Particulars are measured and oriented by generalizations, and generalizations are enlivened and tested by particulars. (30)

How do values, particulars, and generalizations, used in tandem, correlate to equality and justice? Or prejudice.

At the end of the chapter, I wrote a note in the available white space, “As nature writers the query is often why we want to share the outdoors, why we often tread gently. Here is why.”

Abuse of people is never far separate from abuse of land and the natural world … Every story (like every thing) has a context, and every context has a context. (41)

My understanding of the context to which Berry writes is predicated on my life experience, knowledge, homelife, and values. The particulars are the details, each a distinctive point and a matter of interpretation in social conversation or private utterances. Whereas the generalizations are vague, a toss off of words that have no valuable agreed upon understanding. When I had to think about one way to distill this comparison I thought of a blue sky. You and I chatting might have a general understanding of what a blue sky looks like, but do we understand the particular accounting of its color. Might it be the color of a baby boy blanket which has its own generalizations, or might it be a robin egg blue which is more precise as a conversational addition to the context? Likewise, are there clouds in the sky, is the sky hazy, is there a low fog that sits on the horizon even as blue-sky peers overhead because clouds change the blue color. What if the blue sky is seen is through the slit of skyscrapers or conversely, of prairie. These are the particulars of conversation. How our understanding and interpretations can so easily differ. In this example, I use the sky but what about the particulars and generalization spewed about the hard stuff – the difference is prejudice.

There are many themes of Berry that I wholeheartedly endorse. What resonates with me is the guidance he provides and how to distill our own prejudice. He banters a bit the ideas of love/hate. He discusses abuse of people, evaluates dispensable, and weaves them together when he writes about race.

One of the cruelest ironies of postbellum history is that emancipation, in freeing the slaves of white proprietorship, freed them also from their market value and made them individually worthless in the “free” economy—like the poor whites whose “free labor” was already abundantly available, and who thus were individually dispensable. (42)

With so many terms to be acquainted, how does equality, justice, and love—as this chapter is titled—round its way into an understandable position. If I might oversimplify, it begins at home. I can’t help but think what it means to sit around the dinner table in the evening to eat a shared meal, talk about the day, build memories, while also setting expectations of manners, how to talk to one another, and how we talk about others. This seems so old fashioned, but must it be? At my house, dinner is at the table. When we have more guests than chairs people stand, lean against the counter but it is a shared meal and banter of words. Kids are not excluded. It isn’t a conversation for this essay but surely it is the foundation for another one. Because in essence, sitting at the dinner table requires not speaking in generalizations, this is where we learn to formulate our perspective, to make a valuable argument to what it is that we want to depict, what we want the siblings, parents, extended family, friends, and acquaintances to understand. We learn to speak in the particulars of understanding and knowledge, understanding that the questions that surround the presentation are the context to which it is based.

What it means to embrace that the reality that the life of another is not like our own and as such is bound with its own construction of generalizations and context. Thus, how can we define equality for all. Maybe it is as Berry suggests,

Any violence that intrudes between the land and the people extends its damage both ways. (39)

January 26 - Chapter III. Degrees of Prejudice (88 pages)

Berry separates this chapter into ten essays that consider human relationships using the Civil War as a backstop, including his family’s relationship with slaves, a community of black and white bodies, and the nuance of prejudice.

Share Your Thoughts

Reading Berry is to understand he values community. Please share your thoughts in the comment section and we can have a community conversation.

Don’t know what to type? How about what you liked about the first two chapters or what frustrated you. Share a quote that resonates. Maybe something you have learned or any of the principals Berry touches upon. Other possible questions are below.

References

We are reading Wendell Berry’s, The Need to Be Whole: Patriotism and the History of Prejudice. Shoemaker & Company, 2022.

"Every context has a context", Generally speaking, Americans are not good at putting things in context. Most people seem to abide by what I call the "vacuum theory of history." That is pinpointing a specific time went everything went wrong. Whether it is the belief that the start of moral decline in the U,S. began when "they took prayer out of schools." Or more recently, the degradation of political discourse began when Trump came on the scene. Of course there are pivotal points in history, but all those pivotal points have a context. The current state of race relations in America has a four hundred year context that dates back to the pivotal point at Jamestown when the first enslaved Africans arrived. Understanding the context is complicated by the fact that each interpreter of history has his or her personal context through which they see and understand the world. Wendell Berry is no exception to the rule.

I am responding to this starting framing remark about Berry's overarching thinking-writing style "Berry does two things simultaneously. He clearly states and supports his point while also making it difficult for a general reader to understand." It's good for every reader to get clear at the get-go that reading any of Berry's works is NOT for the intellectually and spiritually lazy. You can be a slow reader, a long cogitator and perpetually reflective, but what you cannot be is unwilling to do the work he demands of his readers.