Nature's Reclaiming, an Anthropomorphized Bear, and Moral Lessons

what resonates with me in Andrew Krivak's, The Bear

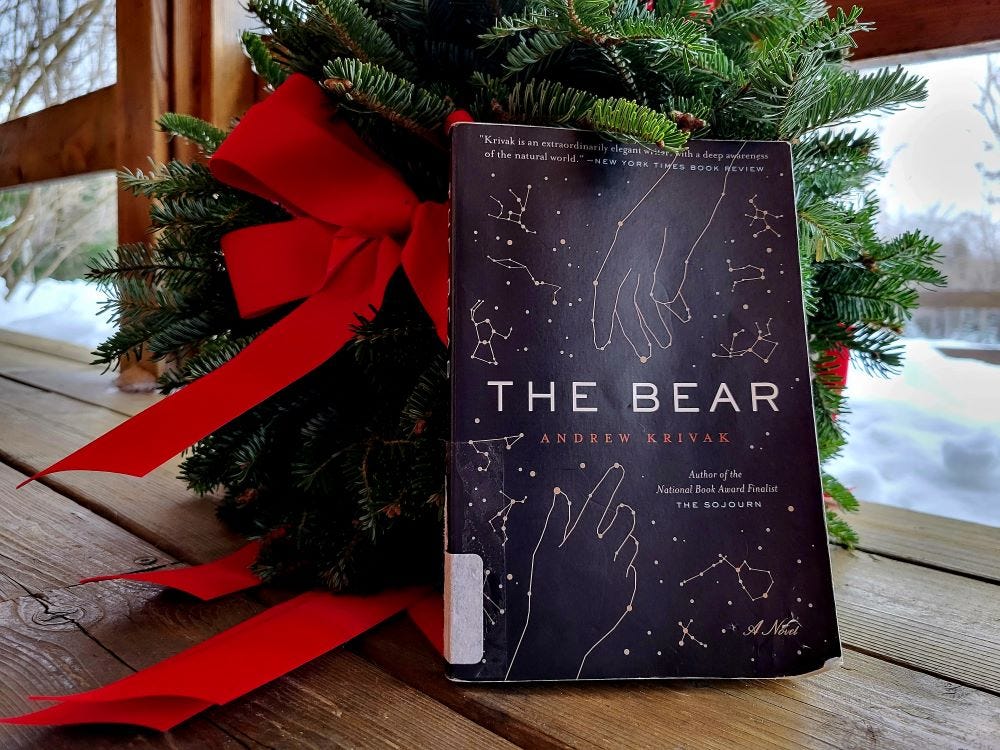

Like everyone else, I have a few favorite books. Andrew Krivak’s, The Bear1 is one them. Always it makes me cry. Its emotional resonance is not of human sadness but something more devoted to what is buried under the snow in a winter forest or what it feels like to drift along the contours of a mountain. In so many instances in my notes I write the word, “significance” but in a most superficial of inquiry because the craft of this Krivak story is the use of minimalist writing. There is much to learn from this book by simply taking Krivak’s words at surface level or pause and dig a bit deeper in the wise storytelling passed from bear-to-bear.

In 2019, Krivak wrote in his on-line journal,

By calling the novel The Bear, I am suggesting that there is hope all around us, if we step back and see ourselves as part of—not the center of—a larger, ever more beautiful and animate world.2

Some describe this read as a dystopia piece or maybe post-apocalyptic. I do not believe it to be either of those, but I can understand how a society that is less and less connected to the land might find the book discomforting. Goodreads uses the word “fable” in its description, and I like that category—but maybe instead of a label, this book should be tried on as a shadowed cloak to tip one’s toe into a new understanding. It is an excellent read that can be completed in one evening or can be savored over the darkest nights in the depth of winter.

Genre: Nature, Long-Fable’ish

Pages: 221

Brief Summary: The Bear begins,

The last two were a girl and her father who lived along the old eastern range on the side of a mountain they called the mountain that stands alone. (13)

What remains of the past are some books, a pane of glass, a set of flint and steel, a compass, and a comb. As the last humans, the story is a journey of survival, instinct, and honor. The path is through living on the land with a dependence on the land as a treasury where animal and plant beings give themselves for human’s survival. There is an undercurrent of hope, of what it might be like to be the last and have little to no history of what was before and to understand a true relationship of the land as not anything but of reciprocity. The connection is not of fear but as an interrelationship. In the forest of this mountain, messages are shared with voices that exist in the background like a breeze until a listener is ready to hear. And of course, there is the bear—as in Ursidae—“… large heavy mammals of America and Eurasia that have long shaggy hair, rudimentary tails, and plantigrade feet ...”3

A Homograph Diversion: Curiously, bear4 in the thesaurus provided me with a handlebar to grasp tightly with respect to this book. It is almost as if Krivak incorporated each of these similarities into a homograph-like comparison. Maybe not, but a great craft consideration.

As in to have

As in to stand

As in to relate

As in to head

As in to carry

As in to hold

As in to behave

As in to haul

As in to assume

As in to pack

As in to lead

As in to need

As in to contain

As in to be

As in to yield

Quotable Take Away:

… you need to be hungry for more than food … Be hungry for what you have yet to do while you’re awake. (178)

Something to Think About:

The girl sipped at her tin cup of pine-needle tea and considered the question, then said she found it hard to believe that all living things needed to speak.

Believe, said the bear. Whether you hear them or not, they need it like they need air to breathe. (121)

A Tenuous Gap of Hearing

To better understand a fable, I reviewed some notes on StudioBinder5 to understand that fables commonly feature animals as characters. Their beings are anthropomorphized to allow the storyteller to explore human issues in a relatable way. The intention of a fable is to impart a moral lesson or ethical message. A good fable bridges the tenuous gap of living and nonliving.

It might be because I feel so sure about an individual’s relationship with nature that her voice is not just a possibility but a palpable presence. I feel strongly that our landscape environment is broken into bits and parcels. It is incomplete as a whole though there continues to exist a (mostly) functioning ecosystem whereby Gaia sustains the requirements of human living.

I spend a lot of time outside and believe that the beings—trees, animals, weather—have routines and practices. In prior postings I have said, nature is not in rehearsal, she is in practice with rules.

The bear shifted and sighed and was quiet for a time. When he spoke finally, he said that long ago all the animals knew how to make the sounds the girl and her father used between them. But it was the others like her who stopped listening, and so the skill was lost … all living things spoke … (121)

What it means to have a voice, an ability to utter words that express or tell stories. What if a voice isn’t words but sounds or movements. Vocalizations that provide emotional support or guidance. Consider all the verbs that surround the idea of movement – swirls, pirouettes, waves. There is squirming, stirring, and bolting. Consider what it means to dart, scurry, or even cartwheel. What about to lift and to drag, to twist or to squeeze. All actions that we see in the layers of leaves, canopy of trees, roots of flowers that surround our places of concrete and hardpack.

Bear reminds us,

The trees are the great and true keepers of the forest, he said, and have been since the beginning. (122)

Imagine rooting in the lifecycle of a tree, its existence several generations beyond our own. Contemplate what it knows and observes in its lifetime and how it might share its knowledge with the beings that follow.

[Trees] never make an unnecessary sound. (122)

Think about this for a moment. How we seek to find no sound, no interruption of silence being so constantly surrounded by non-natural noise. The commotion of inharmonious sounds that squash the natural ones. No wonder humans no longer hear the sounds, the voice of forests and land.

… trees are the wisest and most compassionate creatures in the woods. They will do all in their power to take care of everyone and everything beneath them, when they have the power to do it. (122)

As a moral, “power” and “it” do a bit of heavy lifting here. And this is the weaving potential of the significance within the pages of The Bear—as both bear and bear. Because here is the power of trees and the beings that roam and ramble in her branches, travel past her trunk, or bury at her roots. What she offers is history, a longevity of presence.

When we die, we lose the influence sound offers. To use our voices not for righteousness but for greater good. An honorable path to humans’ continued existence.

Look Back: In 019 – Ten Habits for Self-Rewilding I share ways to rewild yourself. Pick one of the ten to reframe your outdoor understanding. In case you missed the essay -

019 - Ten Habits for Self-Rewilding

I spent hours this past week spitting venomous words on blank sheets of paper that did not deserve the treatment of heavily scratched out phrases, entire sentences, or hastily marked “X’s” of uneven temperament. I wrote on scraps, half sheets, the backside of stories begun, and the back of my grocery list. In one fit of rage I shouted into the Note app …

OMG, Stacy! This book sounds fantastic. Just ordered it at my library. I'd love to link to your post in this month's NatureStack, if that's okay w/ you.

Adding to my list, thank you!🐻