This is the first discussion entry into Wendell Berry’s, The Need to Be Whole: Patriotism and the History of Prejudice.

Share your comments below—this is intended to be a community conversation.

Introduction (16 pages)

… both the land and the people are unhealthy. (10)

This is where we begin Berry’s tome of words. Except it isn’t, but it is consistent with Berry’s decades of messaging. Where Berry truly begins is in the third sentence:

… that white people’s part in slavery and all the other outcomes of race prejudice, so damaging to its victims, had also been gravely damaging to white people, a damage too little acknowledged and probably less understood. (1)

Following an involuntary gasp, I lean back in my chair. For a moment I wonder if I want to flip to the next page because how is Berry equating a damage? Might he be aligning a balance of treatment and outcome to what are racial issues and conversation? How can the white population, particularly a white, middle class, elder man, dare to make a statement that there exists something of common troubles among races?

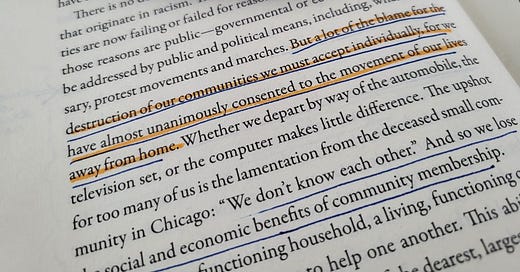

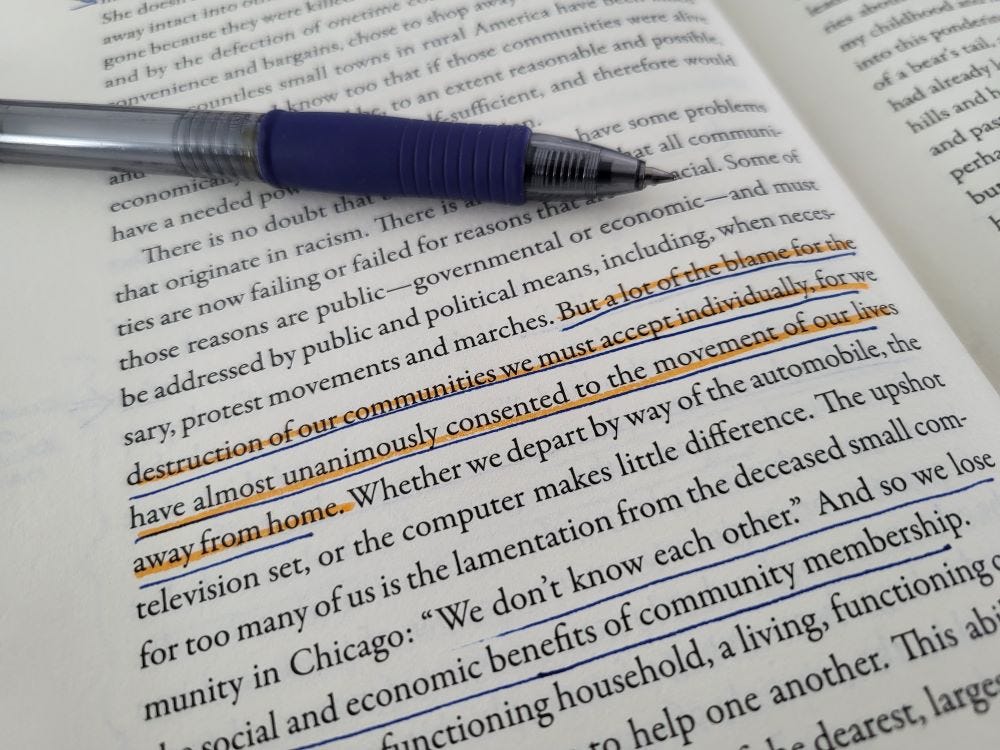

Already I am ahead of myself. Overthinking. Re-reading. Where do I pause with the commas, which clause is connected to … Then, I decide to sink into the discomfort because this is page one and certainly, there exists a perspective to which I am sufficiently inexperienced. I flip another page. Then another. And, though I try not to abuse my books, I begin adding notes in the margins, underlining words, phrases, and adding a squiggle line to passages that I might want to again refer. Because before many more pages turn, I come to understand what Berry wants me to gain, that maybe in our failure to have conversations, to dig into the uncomfortable, we have failed to understand:

… that in our public discussion of racial issues, such as it now is, there was too pronounced an assumption that black people and white people are entirely unlike each other in their history and their problems. (3)

And those two words, entirely unlike, sit on the side because I know there is more.

It feels a bit unsettling to write these words of Berry, but with fortitude I persist and then Berry gets to where I think/hope/want to believe he was headed—community membership. There exists no roundtable discussion to: black and white are a description of individuals as the “least interesting attribute.” (7) No argument that the white treatment was in fact a “debilitating condescension.” (7) Our prejudice permitted slavery. Swatches of black people were forced into slavery conditions. These people knew how, cared for, valued the land as productions for food. People who created a community within their plantations and geographical locations. No evasive excuse bundled in reflection because we know this to be true. In return, we are asked to take ownership and work towards a solution of favoring the value of all persons.

As Berry winds his way through 16 pages the crux of his outpouring is that as wealthy people acquired land, they worked distantly from the actual treatment and understanding of the land. We tend to think of a people in bondage but in essence the bondage has flipped its own script—bondage is on the individuals who cleaned their hands from the soil, who failed to understand how to till, sow, and harvest. Who absolved themselves of working with hoe or stock. Who forget the dust of thrashing wheat, the scent of blood from killing hogs, the numb and bleeding fingertips of picking cotton. What has been lost is not just the care of the land, but care of the community—a network of individuals. Small communities did more than eke out a living constructing individual worth as part of a fraternity with partnerships and fellowship. Reliance built on roles, individual strengths and assimilation of appreciating what is offered as service. Service, look at Main Street. There are the occupations and livelihoods of neighbors. The local grocer or butcher has ground beef from the stockman over the hill. The seamstress tailors your clothes, raises or extends the hem. The doctor knows your ailments with no need for long appointment times or a chart. Communities are places of interconnection. When the farmer and his family leave, storefronts turn dark with dusty windows.

I feel like people will laugh at the very Andy Griffith-like paragraph above (I suggest that the knowledge of an era might be unsettling because of the isolation), but I understand that Berry might be suggesting enslavement is a dichotomy of positions. Those with economic means, build such on the backs of those in less of a position to push back. The cleaner hands financially prosper by their disconnect to the land and its associated landscape. By extension, the reduced connection facilitates a reduction in an ability to self-care. No hands in soil to grow food develops a reliance on others for food. Land bought up from those with the financial means reduce the ability of small farmers to succeed. Economics fills the gap with a goal to make money. What is unconsidered is the cost to the land, its surrounding communities, and environmental decline. Also in decline, health. Wellness is possible because of a relationship with the soil, with community of similar, and dissimilar, and actual caloric nourishment. As more disenfranchised individuals move from their homeplace, and with them knowledge and skills, perspectives for a positive outlook from the food sources of community become a disempowered people. Solidarity as a workforce declines into disgruntled and depressed. Broken are the home communities, goods and services leave, poverty rises, the soul of place fragments. Ultimately, a failure to have faith or trust in a social fabric with a greater good foundation leads to a less patriotic people.

Berry is falling on the sword he has been preaching for years. And this is the conversation I expect from him. As big business gets bigger, as those with lesser means become more economically strained, as bridging the possibility for more profits comes at the creation of “cheap food” or “cheap energy” (13), we as a population become unhealthier. Our lands are polluted, our water is tainted, our food is genetically modified, fewer hands touch soil, grow their own food, and/or can make a living from the food they grow; exploitation sees no end. Berry is imploring the reader to understand that prejudice is not just race relations but a prejudice of labor, of effort, of self-sufficiency to which can be firmly planted at the feet of industrialism and the economy which is not of fairness and shared wealth or even being paid a fair wage but of lining the pockets of a few and the continued ill treatment of people.

The “race problem” began as a rural problem necessarily because it began in response to a supposed agricultural need, and before the growth of large industrial cities and urban civilization. The problem became urban when millions of black people, like millions of white people, moved from the countryside into the cities. (15)

Berry says that the three terms – “race prejudice, race relations, and race problems … [are] talked about somewhat in general terms.” (6) Interchangeable like points of a triangle. Directional markers which I am beginning to understand, effect relationships as a whole. Impoverished is a term with unpaid rent in my mind. Not one Berry uses, but maybe the one I recognize as theme—for now—as an unintended seed Berry plants into a row he wants the reader to understand before turning up the next row of growing tobacco.

Maybe this is not a triangle of points, but instead a line of interconnection zooming without brakes. A train running out of track. Berry has set the track, added points of connection, now in the chapters to come he has to persuade the conversation.

It is possible after reading all the pages of The Need to Be Whole: Patriotism and the History of Prejudice we could very well understand, we cannot blindly wish to leave our past behind.

January 19 - Chapter I. Public Knowledge, Public Language (12 pages) and Chapter II. Equality, Justice, Love (16 pages)

I don’t know how you are reading but my copy has a lot of circles and lines.

Berry begins with a thoughtful consideration of oversimplification and disclaiming of individual personhood. Then he delves into generalizations and particulars. It is okay to feel a bit humble by the end of 28 pages.

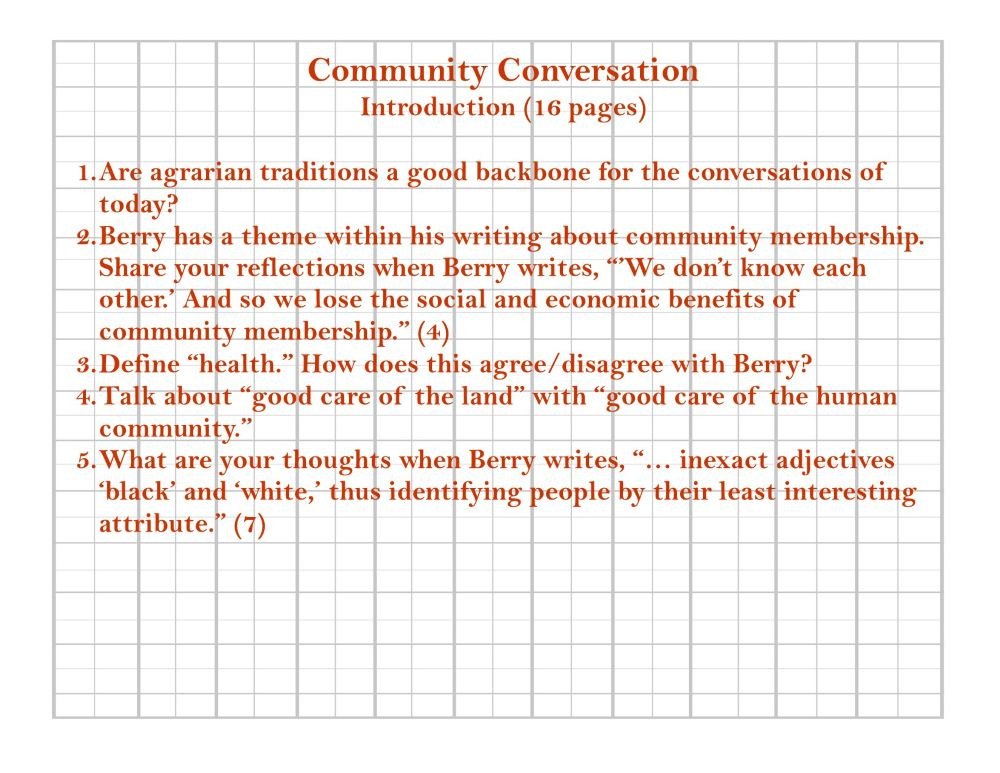

Share Your Thoughts

Reading Berry is to understand he values community. Please share your thoughts in the comment section and we can have a community conversation.

Don’t know what to type? How about what you liked about the Introduction or what frustrated you. Share a quote that resonates. Maybe something you have learned or any of the principals Berry touches upon. Other possible questions are below.

References

We are reading Wendell Berry’s, The Need to Be Whole: Patriotism and the History of Prejudice. Shoemaker & Company, 2022.

Stacy, I am so honored to be part of this conversation and growing community. Like you, I am doing a lot of underlining and making margin notes in my copy. From the introduction, this sentence comes to mind - "Another difficulty that I have had to deal with is that I cannot see race prejudice and the sufferings related to it as special or isolatable problems calling for special or isolated solutions." Berry has taken on a difficult problem and will come at it repeatedly as he articulates his own positions and suggests solutions for his readers.

Thanks for this, Stacy and Dudley, and thanks for the invitation to comment. For me, this piece is what Substack is all about and I want to take the time to connect.

After reading your first discussion entry, my mind has raced this way and that - to places and issues closer to my home in the far north of England than Kentucky. I was thinking about the memoir Unearthed: On race and roots, and how the soil taught me I belong by Claire Ratinon, Claire has Mauritian heritage and lives in England. She also co wrote a pamphlet called Horticultural Appropriation with her partner, Sam Ayre. (I hope it’s okay to point to some of the folk/books I’ve been thinking about?)

Yesterday I was writing a piece about the lure of place (I’ll publish it here on Substack in the coming days but want to record the audio first.) Anyway, place and nature writing are what I read most and I’m anxious, so anxious, about our disconnect from natural place.

People are place, people are nature. Wendell Berry, if I'm honest I know so little about him (have read none of his fiction, have mostly read his poetry and essays and articles) but I know he writes in response to place. When I wrote a comment to your ‘One Sentence a Day,’ Stacy, I said it reminded me of my favourite poem by Thomas A Clark. It’s called Riasg Buidhe. Clark writes in response to place, too. Berry aside, other (American) writers and activists writing about place that I admire (off the top of my head) Robin Wall Kimmerer, Ursula Le Guin, Barbara Kingsolver, Richard Powers.

What resonates most is Berry’s emphasis on the loss of community and its connection to the land. As industrialism grew, as wealth and capitalism concentrated in fewer hands and people left rural areas for towns and cities something essential was lost that just can’t be replaced by modern conveniences. Berry’s nostalgic description of small-town interdependence - the butcher, the seamstress, the farmer - feels quaint, outdated, but resonates, reminds me of the importance of relationships rooted in mutual care and shared labour. In our drive for economic efficiency and technological advancement, have we severed ourselves from the very soil, literal and metaphorical, that sustains us?

Dudley, you wrote “Berry is imploring the reader to understand that prejudice is not just race relations but a prejudice of labor, of effort, of self-sufficiency to which can be firmly planted at the feet of industrialism and the economy which is not of fairness and shared wealth or even being paid a fair wage but of lining the pockets of a few and the continued ill treatment of people.”

....That’s incredibly thought-provoking, isn’t it? it underscores how systemic injustice - whether racial, economic, ecological - are interconnected. Berry’s call to see these relationships as part of a bigger picture feels urgent in today’s fragmented world.

Ultimately, Berry is asking us to engage in a conversation, a nuanced, uncomfortable and deeply personal conversation. He reminds me that we can’t leave our past behind, not if we hope to build a healthier, more equitable future. This is a call to responsibility, not just to the land or to one another, but to the…. soul of community itself. Berry is asking us to remember what it means to belong: to a place, to a people, and to a shared history, however painful that history may be.