Chapter V - The Need to Be Whole

Two-way harm, sacrificial love, and to have a voice - considerations from Wendell Berry

This is the fifth discussion entry into Wendell Berry’s, The Need to Be Whole: Patriotism and the History of Prejudice.

This week there are two essays. The first from Sarah, the second from Stacy.

Share your comments below—this is intended to be a community conversation.

Sarah Savage is, among other things, a long-time hiker, a writer, and an avid world traveler. She has spent more than half a century escaping on foot to the quieter places – meadows of flowers in Colorado, dirt tracks in Alaska, horse trails in New York, and the peaks of the Rockies – to watch and to write. With Observations Afoot, Sarah combines her analytic side with her writing skills, her years of sitting quietly in the mountains with her experiences in other countries and shares the results. Join this writer, hiker, and world-wanderer as she explores this life, one moment at a time.

Chapter V. Forgiveness (72 pages)

Sarah’s Essay ~ Pecos National Historical Park and Chapter V: Forgiveness

On a windy day in February, Tom and I took quiet back roads out of Santa Fe and wound through pine forests for almost an hour before arriving at the Pecos National Historical Park outside the tiny town of Pecos, New Mexico. The park commemorates a Puebloan community that existed for almost 500 years at Glorieta Pass between the Rio Grande Valley and the Great Plains.

I’ve been to Chaco Canyon countless times, and I’ve visited the Aztec ruins in the middle of the town of Aztec. I’ve soaked in the general timeline of the ancestral Puebloan culture, but even standing in the darkness of a reconstructed kiva in Bandelier or studying petroglyphs etched into remote cliff faces, my experience of these communities has been mostly academic. I understood what I read and saw, but I usually couldn’t imagine the day-to-day lives of individuals.

Pecos was immediately different. Just outside the visitors’ center, we stopped at the first sign on the self-guided walk through the site. It showed what the area may have looked like almost 700 years ago when Pecos Pueblo was a busy community where people from all over North America and Mexico came to trade shells, tools, captives, and turquoise.[i] I read the brief description on the sign and then compared the image to what I saw in front of me—a large open field bordered by coniferous trees, and a ridge with what looked like a low wall along the top. It was easy to imagine that field filled with travelers and tipis and the ridge covered with multi-story pueblos.

“This is what it used to look like,” I told Tom, gesturing at the view in front of us.

I was stating the obvious, struggling to communicate what I felt. The people were gone, and the buildings had fallen down or been destroyed, but the collective soul of the community seemed to still be there, invisible but present.

We followed the path to the ridge and found the ruins of kivas and sleeping spaces overlooking a valley filled with healthy juniper and pinon pines. In the wind I could almost hear the voices of past people going about their lives, gossiping while they ground corn, scolded children, made plans for a meal. Were there trees in the valley then, or had they been cleared to make room for crops? Would the creek winding through the bottom of the valley have been visible from where I stood? I wanted to sit amidst the ruins and bask in the made-up memories of long-ago life, but it was too cold to stay still.

At the far end of the ridge the remains of one of the four Pecos churches loomed. As Tom and I wandered among the buttressed stone foundations that once supported walls up to twenty-two feet thick, we read the signs explaining the arrival of Spanish missionaries in 1598, their abuse of the Puebloan people for eighty years, the battle that briefly repelled the invaders, and the gradual decline of the community until the last of the Pecos people walked away to join the Pueblo of Jemez in 1838.[ii] Except for briefly overthrowing the Europeans, the story was familiar and heavy feeling.

In Chapter 5 of The Need to Be Whole, Wendell Berry writes about the importance of forgiving and being forgiven. He builds his case around Civil War participants, specifically Robert E. Lee, but I consider how Berry’s ideas might apply to Pecos. Should I forgive the missionaries who disrespected the Pecos culture and persecuted the people? Should the Pecos people forgive what was done to them? I immediately feel resistance in my body, as if one of the thick stone walls from the church has materialized inside me.

In a recent column for the New York Times, therapist Lori Gottlieb said, “Forgiveness has become a kind of cultural mandate that is somehow supposed to set you free,” but “There are a lot of things that just simply aren’t forgivable.”[iii]

I’m not in a position to decide whether the ancestors of the Pecos people should forgive what was done to them, and I can’t find it within myself to forgive those ancient missionaries. So, what are the alternatives? Is my only option to accept feeling guilty about atrocities committed centuries ago?

Surprisingly, Berry offers a way forward.

… [P]rejudices are powerful, powerfully felt abstractions, by which people evade or sluff off the complexity of human nature and human lives. To these prejudices, individual persons become types or specimens, crowded together and anonymous. People can escape such anonymity only by talking, working, or neighboring together for a while, maybe for a long time. (179)

This makes sense to me. It’s about nurturing relationships now, connecting with one living person at a time, having meaningful conversations and finding common ground as individuals, not as representatives of amorphous cultures. I want to start immediately, to meet someone and learn about each other, but I’m alone while I write this, so I resort to imagining past individuals I would have liked to have known—a woman weaving sandals while her young son plays nearby. She’s tired, but proud of the life she’s building with her new family; a girl on the brink of adulthood, thinking about a boy she met recently. If she marries the boy, she’ll be seen as an adult by the nearby circle of women preparing food for an evening meal, but it will also mean giving up days playing in the creek, free of responsibilities; a man and a woman standing on the ridge in the wind, talking so clearly I can distinguish words in a language I don’t speak.

In recognition of Pecos Pueblo, the Pueblo of Jemez often visits in August to celebrate mass and to honor the place through traditional dances, prayers, and blessings.[iv] Maybe that’s why the area feels so serene, alive, and welcoming. Whether or not they’ve forgiven past behaviors, the people still remember and revere the pueblo and the place it had in their history. Our visit to the park helped me understand this, and when forgiveness isn’t possible, maybe understanding is a start.

[i] National Park Service. “Mighty Pueblo .” Pecos National Historical Park Walking Trail Sign, Pecos.

[ii] Sarah, Maher, editor. Ancestral Sites Trail Guide, Western National Parks Association, Tuscon, AZ, 2018.

[iii] Dunn, Jancee. “On the Couch with Well’s Resident Therapist.” The New York Times, The New York Times, 17 Jan. 2025, www.nytimes.com/2025/01/17/well/therapist-advice-lori-gottlieb.html.

[iv] Sarah, Maher, editor. Ancestral Sites Trail Guide, Western National Parks Association, Tuscon, AZ, 2018.

Stacy’s Essay

Sitting with a cup of lukewarm tea and copy of another version of this essay waiting for revision, Dan’s comment popped as a message on my phone. Before I finished reading its few lines, tears streamed down my face and wetted the draft. It is the simple words that often inter a cautious, but truthful resonance – “It looks like you have found your people.”

It is wholeness that Berry seeks for each of us to find. This pivotal arrival means to stand center with our strength of character.

In order to go with your people it is necessary to have a people with whom you identify and to whom you feel that you belong. To have a people in this sense you must have a place in which you and they have lived together for generations, and to which you mutually feel that you belong … people’s attention will have begun to shift from that which belongs to them to that to which they belong. (203)

Note: I insist that we have passed a time that equals “lived together for generations” and submit instead an idea of seek and find and surround. Nevertheless, I do believe we can return to small community ways and means if there is sufficient want.

Dan reminds me that the root of this effort is to have a meaningful, maybe even instructional, conversation. In this small responsive community that is reading, each is a part of an assembly. We may not agree with all the words written from Berry or each other, yet it is significant to understand, each of us lives an individual life. What it means to embrace a point of view and to lighten the load by allowing contrary emotions to fall away. In a larger scope, what does it mean to push away a non-conciliatory response, this does not mean to disregard or even condone, but to unchain ourselves from the shackles of our own reflexive reaction.

When our minds are clear, our eyes are free to look around and see where we are, and who all and what all are there with us. (235)

It fascinates me with the approach and arrangement Berry builds beginning in the “Introduction,” with the first paragraph.

… what I have most remembered of that conversation is my dissatisfaction, with my own part in it. (1)

Am I the only one who also feels dissatisfaction in my correspondence or self-questioning?

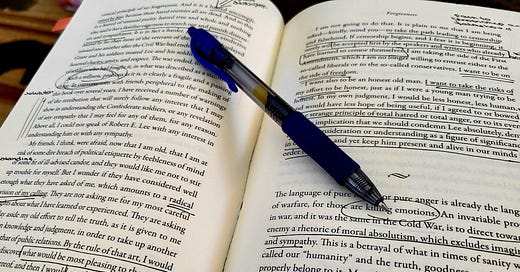

I am struck by this confession the more pages I read, because The Hidden Wound (which I have not read but is in the book cart for later examination) is now fifty-plus years old. Written, I dare say by a mere child author who has had a long time to examine his own convictions and to feel comfortable enough with who he is to stand by the words he writes. As the book continues Berry weaves ideas for consideration—some (for me) feel very possible, others not so much. I mark passages with words like THIS, or Use, or What IF? There are also passages with ?? or generalization unbecoming, impossible to quantify, or one of my favorites Berry is being naïve. I also mark passages with Berry humor. The point being, there will rarely be a book, this is not a story, to which every reader will agree with every word/passage/theme.

Nearly 500 words into this essay about a chapter that is 72 pages long, broken into nine articles, and there is a lot I want to talk about which is greater than what I want to say. I wish for a dinner table to banter sentences that strike me as part of a larger conversation, which is exactly what Berry intends. I have quotes that need a home. I am in a mood that is not feeling generous, and this feels antithetical to this chapter where I laughed, groaned, tapped on Google, and shared excepts and asked questions, received replies and deliberated. This chapter builds as a ladder of tiny steps. A ladder within the platforms of a scaffold. Maybe, think of this chapter as the layers of a monument that rises, requiring a tilt of the head to see the top. A monument that looks down from its grand bigness.

What does it mean to be whole.

Forgiveness: release from the guilt or penalty of an offense (i.e. amnesty)1 which is a bit different from forgive: to cease to have feelings of anger or bitterness towards (i.e. pardon).2

In “Forgiveness,” the time Berry has taken to be the attentive gardener moves the reader from why to begin the work. I can’t help but feel that forgiveness is much like the faith that happens when seeds are sown into the soil. Seeds have about 48 hours between when they are dampened to send out roots and to dig their way upwards to the sun that is so necessary for growth. There exists a tremendous amount of faith when a farmer waits until green pokes through the dirt. I wonder if Berry feels when he writes this chapter that he has planted the seeds and now it is time to reap a bit of the harvest.

If you can approve of a war and yet imagine your enemy in likeness to yourself, there is no resting in peace. (237)

Insert a different word for war—conflict, disagreement, strife, altercation—and the sentence still works. Wholeness is to be complete but is this an absolute? Is wholeness to be free from the ailment of anger and/or hate or to seek a different scene through which to view the war?

In this chapter Berry entrusts the reader, with examples that almost feel like a curiosity to me. I mean General Morgan’s Mare is a specimen of history rewritten, and the sexism, on behalf of a horse is almost laughable … almost. Of course, the removal of General John Breckenridge Castleman’s monument is an example of appeasement, but with dishonest judgement. Before I began this book those that have read it referred to a remembrance about Robert E. Lee but there seemed to be little additional comment other than it stuck out.

Using Lee as a discussion in defining the union of family, land, and patriotism is to remove generalization, add specificity. It is my opinion that any reader has an opportunity with this abstract to come face-to-face with how to hold firm, remain steadfast to that etched within the veil they present to the world or whether to soften their own edges a bit. Berry uses a painter’s brush beseeching the reader to be sufficiently open-minded, to be strong enough to understand the wholeness to which he has been attending.

Berry pounds the table with finding a place to belong, a place of people with a community kinship and supportive underpinning. Berry uses the term fidelity on page 215, when he begins to more strongly steer the reader towards the idea of whole. Fidelity is an accuracy in details which is a stringent guideline when exactness is skewed by perceptions and generalizations and oversimplification. To keep an imagination whole, he pushes, is

to offer understanding and sympathy to enemies, sinners, and outcasts: sometimes to people who happen to be on the other side or the wrong side, sometimes to people who have done really terrible things, sometimes to people judged to be low-down or beneath notice. (215-216)

Where is your place, your people, where you belong? Or is your place currently one of superficial friendliness within the guardrails of a prescribed conversation? What might be done today to frame a neighborhood that bolsters one another in wholeness—one of forgiveness but … health as the natural or normal condition of our bodies and the world. (10)

What it means to,

… recognize wrong and to do what is right: to become in the finest, fullest sense human, even when it is “too late.” (222)

I think I’d like to not just believe in but tend towards my personal need to be whole.

February 16 - Chapter VI. Kinds of Prejudice (20 pages) and Chapter VII. Prejudice, Victory, Freedom (24 pages)

There exists no simplicity in discussing prejudice and in these coming chapters there exists conflict of patriotism, the condition of a peon, usury, and the work is dirtier than before.

Share Your Thoughts

Reading Berry is to understand he values community. Please share your thoughts in the comment section and we can have a community conversation.

Don’t know what to type? How about what you liked about this fifth chapter or what frustrated you. Share a quote that resonates. Maybe something you have learned or any of the principals Berry touches upon. Other possible questions are below.

References

We are reading Wendell Berry’s, The Need to Be Whole: Patriotism and the History of Prejudice. Shoemaker & Company, 2022.

So many familiar stories here that I grew up with, particularly the ones relating to John Hunt Morgan and Robert E. Lee, and then there are the examples from Homer, Shakespeare, Milton and Merton. Forgiveness and Love are every bit as powerful, even more so, than war, hate and fear. It is in this chapter as Stacy says, that Berry "begins to more strongly steer the reader towards the idea of whole." And toward love of place - on page 235, where he writes "Love for that place shows us the work that it asks us to do in order to live in it while seeing to its need, and ours, to be whole."

When I first read this chapter three years ago, I had no idea that we as a country would be facing what we face now, or that we will need to forgive, not the criminal perpetrators, but the ordinary people with whom we have disagreed for so long. There is no going forward if we cannot understand both sides of our story, and begin to work together to heal the land and ourselves.

Just wanted to pop in an essay that Hadden Turner's from Over the Field, writes about the cost of reading Wendell Berry. I like the entire paragraph that this sentence is found in.

... Mr. Berry has devoted his life to writing and to farming (the visual and earthy representation of his words) — to make us think.

https://substack.com/@overthefield/p-143597158