Chapter VI and VII - The Need to Be Whole

conflict of patriotism, the condition of a peon, and the work is dirtier than before is a lot to consider from Wendell Berry

This is the sixth discussion entry into Wendell Berry’s, The Need to Be Whole: Patriotism and the History of Prejudice.

Share your comments below—this is intended to be a community conversation.

As I sit down to write the essay for this week, I find it difficult to separate myself from the words of Berry and current times. I have come to feel my writing has taken a darker edge and it is a bit disconcerting and not something I can blame on Berry.

It makes me wonder, have we made any progress in the century-plus since the North and South entered a four-year war that on the surface ended slavery but (arguably) brought about something less savory. Who can say that the division of current days might have come on their own. A meandering along a different pathway with the same outcome—one that sustains a tolerance for the exploitation of people.

Chapter VI. Kinds of Prejudice (20 pages)

This chapter feels a bit disconnected, causes me to stumble, even as Berry repeats a few points clearly stated elsewhere. It is the opaqueness that isn’t really opaque. Berry moves forward a distinction of three kinds of race prejudice: as sanctioned by law, as conventional or customary, as a personal prejudice in a way that is unambiguous at the chapter’s conclusion. I might be able to put forth an argument that Berry did not need this chapter, except that it does have valuable inclusions for an intellectual thought process—did the outcome following the Civil War bring about more damage through the lack of anticipation of what would happen when four million black people were freed from the bondage of plantations and slave owners? Bondage is the key word here.

There are associating cords within this chapter that need to be a part of the conversation. The first comes from the idea of defending, as a principle of prejudice.

… they conceived themselves to be defending their families and their people, their homes and their homelands. (249)

Two aspects of this quote give me pause, one they conceived and two, defending. It isn’t that I have a problem with the statement, it is simply that what is the alternative? At the most basic level, each of us is defending something and I want to argue that too many of us are not defending that which is most important. Mine is an oxymoron statement, maybe Berry’s is as well, or maybe that is the problem, because what falls in line is the understanding that one must do what needs to be done to defend what they have. Defend honor. Defend the home. Defend the children. Defend the country’s boundaries. What is incompatible is the conceiving which leads back to opinion, which may or may not be supported by right and wrong, or knowledge and truth. And I understand that is a mouthful of a sentence, because to defend and/or to conceive is a conundrum which supports all mis– steps, understanding, intention, interpretation, judge, guide, characterize, trust.

The second comes from Shelby Foot and elicits a barrage of personal unnecessary commentary that for brevity I have deleted and begin here instead.

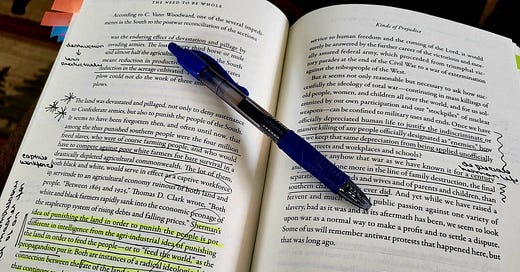

To hurt the people, the land itself was hurt … (253)

and what quickly follows,

Sherman’s idea of punishing the land in order to punish the people is not different in intelligence from the agri-industrial idea of punishing the land in order to feed the people—or to “feed the world,” as the propagandists put it. Both are instances of a radical ideological disconnection between the fate of the land and the fate of the people that continues to plague us and to grow worse. (254)

How much or how can we continue to endure devastation and pillage? Both of which perpetuate a social and physical consequence. Which leads firmly into the concept that Berry is powerful in his telling—if the reader remains with the tethered connection of the three types of prejudice—a captive workforce. This is much of what he speaks about in the remainder of the chapter. A steady cantered reasoning that feels as constricting as the two words when put together. How do we break through the ever-steepening ladder of injustice? It is the word peonage that hit me like a slap in the face, even while I still reel from a captive workforce.

Black and white serve as a captive workforce following the Civil War. Before the Civil War, black bodies were economically valuable by their owners because they could be sold. When no bodies can be sold, the conflict of class and race could only intensify. The number of workers for any job has limitations. With those limitations comes competition. With competition comes resentment and since there are plenty of humans, black and white, to exploit, economics win because payment does not have to be a fair distribution of a profit and loss worksheet. What exists is no bargaining power, an exploitive agricultural economy, and unsettlement.

The Confederacy was destroyed and the slaves emancipated in only four years, but in the 160 years from Lincoln to Biden, nothing has effectively limited the power of too much money. (251)

Politics is where I do not like to put my shovel of effort, but we are eight years past the Obama administration and this quote is not outdated. We have depreciated ourselves—remember Berry speaking of better keeping in Chapter II or the degradation of degrading work in Chapter I, which followed the painful paragraphs of disclaiming an individual personhood with our individual rootlessness? The workforce is captive.

By the end of this chapter, we know the Civil War ended slavery but not injustice. We learn about overburden and understand that with people bound as laborers in servitude, and just one result is a limitation of personal protection. Who then advances and advocates for a remodeling of “work?”

It is easy to overlook this sentence, even its consequence.

Too many of us appear to have decided that all our problems can or should be solved by the government. (266)

But did you also miss these two which might be an important to consider with a historical lens?

But the end of the war in victory for one side and defeat for the other can hardly be guaranteed to destroy the identities or allegiances of the two sides. … Once the defeated are scattered, there is no way to keep them subdued. (256)

Chapter VII. Prejudice, Victory, Freedom (24 pages)

Three quotes back-to-back and then options.

Because ‘the better people’ invariably think themselves ‘ too good’ for it, physical work was a first assigned to slaves or peasants or the ‘working class,’ who have been replaced so far as possible by mechanical, chemical, and other technologies. (287)

Our solutions, so far, to the problem of slavish or menial work, and our wish to do none of it, are themselves forms of enslavement more damaging and more permanent in their effects than the problems we started with. (288)

And for the sake of freedom from certain kinds of work, we have seriously degraded the creaturely commonwealth of earth, water, and air, and ourselves along with it. It is true that if you are black or poor or rural you are likely to live closer than some others to the sources of pollutants, but in general our degradation of the natural work and all of its goods and services afflicts us all. (288)

So where is victory and the freedom? I like this quote from Michael Pollan. Garden can be replaced with dirt or land or ground or earth.

The single greatest lesson the garden teaches is that our relationship to the planet need not be zero-sum and that as long as the sun still shines and people still can plan and plant, think and do, we can, if we bother to try, find ways to provide for ourselves without diminishing the world.

That is where we begin. We take back the dirt, the land, our relationships. We demand better. We force better. We evaluate the life we have currently and dissect to the true pockets of joy and probe into the glares of misgiving. This is option one, the one I hold most firm as purposeful. Why? because I do not believe idleness is the objective. I do not believe it is the point of being here, of being born. What does one do with idleness? What do we do within hours of inertia but waste?

Option two and three are intertwined. I think of these as the contingency plan in at the back of a shelf with cracked binders and yellow edged papers already sketched and outlined for implementation but forgotten. Victory and freedom come from self-worth.

It might be that Prof. Ogletree’s program could be turned to repair of both land and people by means of reconnecting one with the other by the good and satisfying work once known as “husbandry.” (283)

I might be argumentative here, but might these programs be a rebirth, of sorts, of the New Deal CCC programs (something better than the failed American Climate Corps) where working with hands and tools, feeling the contours of the land, being a part of building structures that lasts. Sure, I am thinking—literally—of small pavilions and rocky steps that led into the woods. Workers that flagged and marked pathways with sidehill and drains to offer a less sedentary people complementary physical exertion with physical sensations, observation, and relationship. The land and humans, alliances of memory, and knowledge—the samaras of a maple are edible, so are the sweet berries of a mulberry, but not the seeds of a ripe pawpaw. A relationship with the land by being in the land—a nature-placed relationship.

Let’s get back to job training. Maybe the physical kind that creates muscle instead of pale skin, soft fingers, and flabby asses. Let’s support outdoor education and practices that trend towards a balanced, long sustaining life on earth. Berry does not insist on the sentences above that I want, even demand, but he does reference Professor Charles Ogletree1 who is referenced by Ta-Nehisi Coates2 (much of this chapter is about reparations) with an idea that we need,

… a program of job training and public works that takes racial justice as its mission but includes the poor of all races. (282)3

With a backlog of work, good work and meaningful work in the United States might we begin with public work training? To support freedom, we must make different choices, alter our mindset, and retool our practices, even our comforts.

It would be worth time for me to write a long essay simply on the Bill of Rights for the Disadvantaged,4 referenced on page 274. Consider the idea that equality is not charity, it is fairness.

Part of our wholeness is to recognize our humanity and to honor with a resolve of truth—we all deserve to be greater than the inequity of our parts. I believe it needs repeating at the close of this week’s writing:

… all that we hold dear depends upon our determination to hold ourselves as equal to one another. (17)

February 23 - Chapter VIII. Work (90 pages) - the first nine essays

The first seven are Berry’s offering as an agrarian sampler, a gift of tradition and old land hunger.

Share Your Thoughts

Reading Berry is to understand he values community. Please share your thoughts in the comment section and we can have a community conversation.

Don’t know what to type? How about what you liked about this sixth and seventh chapter or what frustrated you. Share a quote that resonates. Maybe something you have learned or any of the principals Berry touches upon. Other possible questions are below.

References

We are reading Wendell Berry’s, The Need to Be Whole: Patriotism and the History of Prejudice. Shoemaker & Company, 2022.

"Berry speaks about the sympathy he feels for Confederate soldiers. How does his position sway or dissway you from a viewpoint you have? Another way to look at this question is Berry's consideration of patriotism and nationalism from the Civil War."

Stacy, this question you pose at the end of the essay hit home, just as did reading Chapter V and Berry's earlier recounting of the difficult choice Lee had to make in going home to Virginia. The history of the Civil War that I grew up with was written in black and white, or should I say blue and grey. Two sides, one right, one wrong. When I first came to Maine, I was shocked to find in the Camden town square a statue of a Union soldier dedicated to 'The War of the Rebellion," as if it had been a problem so minor and so easily fixed.

I'd never thought about what it would be like to have one's native land invaded, and what one would be forced to do to defend the small farms and towns that made up most of the South. Sherman's March to the Sea and then through the Carolinas was a horror. And in the end, we are left with persistent racial and economic inequality, of industry defeating agriculture. I will be reading Chapter VIII, "Work," with an eye toward possible solutions, because there is still so much work to be done.

What I'd initially intended as a comment turned into an essay, which you'll see soon enough over on my Substack. This kind of community you've fledged makes Substack very worthwhile for me, so thank you heaps.